I picked up some unusual travelling literature on a recent trip through Namibia, a book called ‘Faraway Sandy Trails’ written by Lily Marion Newton more than sixty years ago. It gave me the opportunity to compare routes and find amusing and interesting anecdotes about the country and the days of travel before organised tourism and tar roads.

The chapter about Duwisib Castle, 80km south-west of Maltahöhe, piqued my interest. The century-old castle built in the Namibian countryside and the tale of its occupants had always intrigued me.

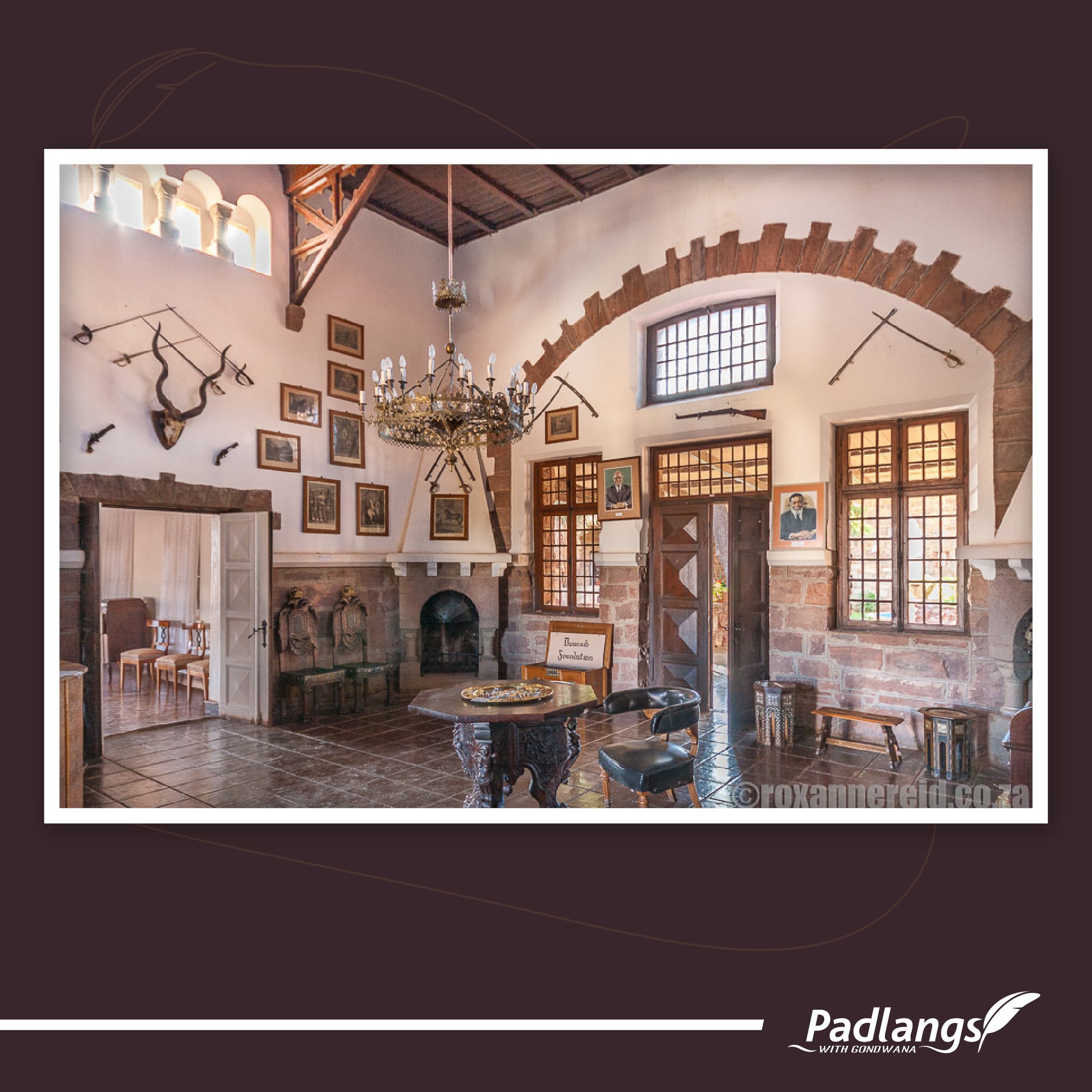

Some accounts of the story are more colourful than others, embroidered with the romance of time, and as you walk through the castle’s vestibule glancing at the crystal chandeliers, pistols, swords, sabres and prints of horses, you are left pondering the real story behind the thick walls. Curtains waft gently in the warm breeze in the adjacent bedroom simply furnished with a heavy wooden cupboard and narrow beds, the citrus trees flanking the building scent the air and a cool peace pervades the inner courtyard.

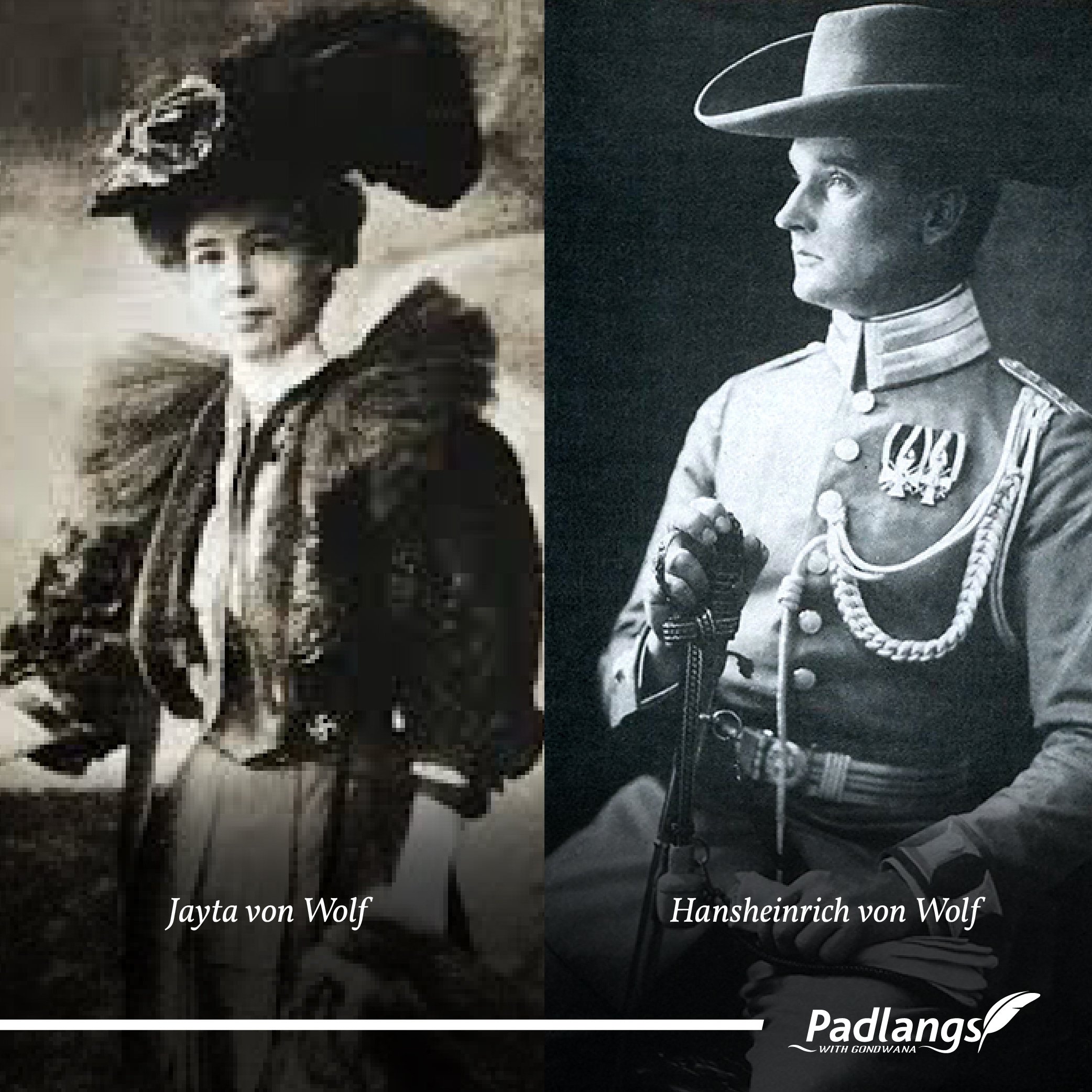

The display of wealth, elegance and old-word charm was clearly visible when Lily visited and wandered through the rooms in awe. I dipped deeper into the history of Duwisib and discovered that the castle belonged to Hansheinrich and Jayta von Wolf and was built in the early 1900s. Like many young German men at the time, Hansheinrich had volunteered to join the Schutztruppe in German South West Africa in 1904. Born in Dresden in 1873, he was older than most and had more than a decade of military experience under his belt.

In April 1906, after the Schutztruppe had clashed several times with Nama leader Simon Koper and his men in the Kalahari, Hansheinrich returned to Germany. There he met and became enamoured with Jayta Humphries, the step-daughter of the American Consul General. The couple were married on the 8th of April 1907 and by the 25th they were aboard the mail ship Windhuk, bound for Swakopmund. When they arrived, they travelled by train to Windhoek where Hansheinrich applied to purchase several farms. He was granted Schwarzschaf-Duwisib, two plots with a total of 20 000 hectares of land, at the price of 40 pfennig per hectare.

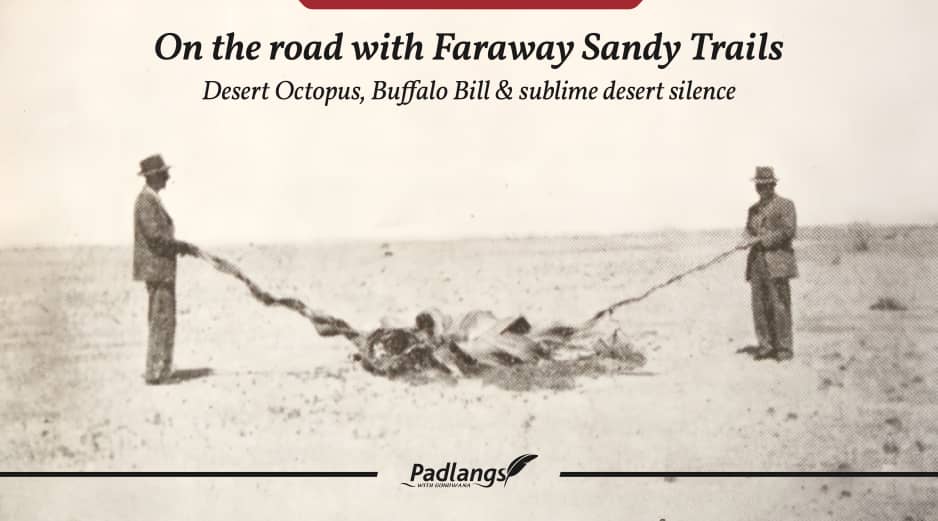

It will never be known why the Von Wolfs chose to build a castle as a home in the African countryside, that secret remains with them, but they commissioned architect Wilhelm Sander for the project. Besides local stone used for the walls, all other materials had to be shipped from Germany and transported the 300km from Lüderitz by ox-wagon. While their elaborate home was being built, the couple lived in tents on the property. They travelled to Germany at the end of 1908 to appeal for more land (they were granted another 30 000 hectares) and to select furniture for their new home, returning in 1909 in time for the completion of their castle.

The Duwisib farm grew over the years and besides cattle and sheep, Hansheinrich acquired a number of fine horses for his stud farm, which was well-known in horse circles around the country.

Fates changed dramatically in 1914 at the onset of World War One. At the time, the Von Wolfs were aboard a German ship, which diverted its course to dock in Brazil. There are several stories of how they managed to make their way back to Germany. One of the more entertaining narratives describes how Hansheinrich hid in Jayta’s wardrobe trunk aboard a Dutch steamer to evade the British naval officers.

In 1915 he was reunited with his former regiment in Germany, only to meet an untimely end in September 1916 when he was mortally wounded in the Battle of the Somme. Jayta never returned to Duwisib.

The short-lived story of Duwisib remains an enigma as does Von Wolf’s title. Although he was referred to as Baron von Wolf and was born into a respected Saxony family, Hansheinrich was apparently not a baron. The title was possibly adopted or bestowed upon him because of his lavish lifestyle and because he did, after all, build a castle and become a land baron.

The castle passed into the hands of the Murman family in 1920 and was later sold to the Thorer group. In 1979, it was bought by the South West African government to be preserved as a national heritage site. Today, it is managed by Namibia Wildlife Resorts and its doors are open to visitors who wander through its vast rooms as I did and as Lily had done fifty years earlier.

At the time of Lily’s visit, she and her husband were taken on a tour through the castle (which she referred to by its German name ‘Schloss Duwisib’) by the manager of the property, who lived there with his wife and children. He led them through the hall and up the steep, narrow stairway to the gallery showing them where the orchestra had sat when the Baron entertained. And when they passed through a small room on their way to see the expansive view from the balcony, he apologised for its state, explaining that his wife used it as her sewing room.

The presence of the place and its story also affected Lily. She wrote: ‘We left that lonely castle not long before sunset and Charles and I were still in thought among the people of other days who had almost been brought to life as we walked in their steps and saw their possessions. Perhaps we half expected to see the Baron in his carriage driving recklessly to a party in the little town; or maybe he and his Baroness on their magnificent horses would pause for a moment on the ridge before disappearing into the lengthening shadows between the hills!’

They visited again a few years later and found that nothing had changed. ‘The Schloss stood dreaming in the morning sun, dreaming of those days . . . when Baron von Wolf’s receptions filled the rooms with laughter and song; and the hooves of his horses thudded and echoed in the valleys around.’

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT