By Ron Swilling

I picked up some unusual travelling literature on a recent trip through Namibia, a book called ‘Faraway Sandy Trails’ written by Lily Marion Newton more than sixty years ago. It gave me the opportunity to compare routes and find amusing and interesting anecdotes about the country and the days of travel before organised tourism and tar roads.

The welwitschia must be one of the most unusual and wonderful desert plants and the short trip from Swakop into the Namib-Naukluft Park to visit the Moon Landscape, Goanikontes and the Welwitschia Plains is one of my favourites. When Lily and her husband Charles were visiting the coastal town, they were told that the Welwitschia Flats was the place to see them. They made arrangements to accompany a friend in his truck, but when he fell ill and the trip was cancelled, they decided to set out nonetheless in their faithful American sedan that they called Abbie, who ‘was being trained to negotiate rough and as-they-come roads’. Two of Charles’s colleagues went along, Jaysee and Bill, nicknamed Buffalo Bill because although he had lived in the country his entire life insisted on calling wildebeest, buffalo.

Lily writes: ‘We set out, quite a merry party, following the road to Walvis, then we turned in the direction of the Swakop River bed and the farm Goanicontes (sic), but instead of going down to the farm we drove straight on, more or less skirting the left bank of the river, into the Namib Desert.’

On they went but were unable to find the Flats or the welwitschias. It was not yet hot, there was no-one else in all the wide circumference and Bill was softly singing in the back. Eventually they thought they saw a house in the distance. ‘It was; and the young man there seemed to convey that it was quite the ordinary early morning thing for a carload of people to pop up out of the desert and ask him if he had seen any Welwitschias about – as if they were stray cows!’ They enjoyed a cup of coffee with him before he directed them to a faint track between two ridges that led to the welwitschias.

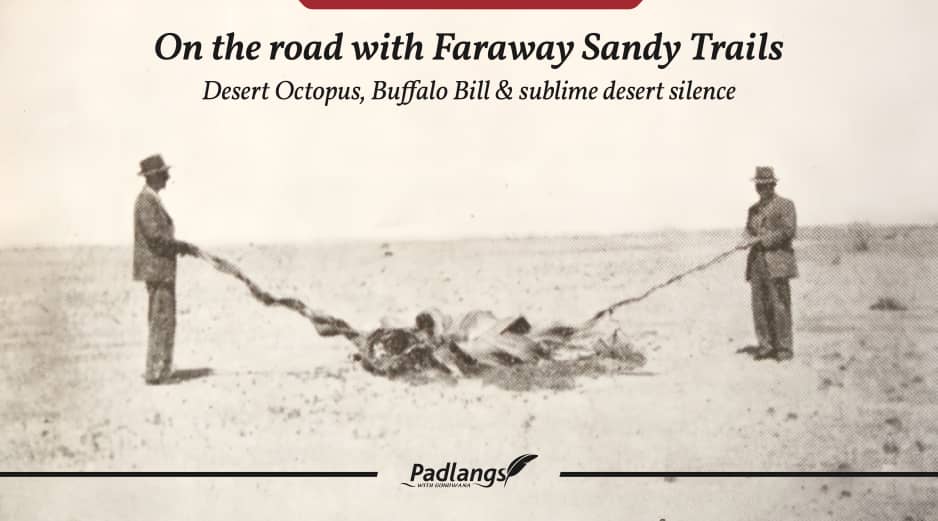

Lily describes how from the outer edges of the knobbly stem or trunk grow two leaves, ‘the only leaves the plant develops in its lifetime which under ordinary conditions seems to be centuries. The winds of the desert are frequent, strong and frightening, and they rip and tear at these leaves until there are a great number of strands. These writhe and curl in the wind and give the impression that the pine (sic) itself is crawling across the sands, hence its alternative name: “Desert Octopus”’. She adds how she took a photo of Charles and Bill holding the ends of the leaves of the largest one (something not allowed today!), which was about twelve feet in length.

The group walked around appreciating these incredible living fossils with their orange-red cones which baffled scientists as to their taxonomy, having characteristics of both angio- and gymnosperms, until they gave the plant its own family in the small order of gymnosperms, the Gnetales. It is no wonder that when Austrian botanist and naturalist, Friedrich Welwitsch, first came across the welwitschia in southern Angola in 1859, he fell to his knees, later writing: ‘I am convinced that I saw the most beautiful and magnificent botanical wonder that tropical southern Africa can present’. The plants were named ‘Welwitschia mirabilis’ in his honour, with the inclusion of the Latin word ‘mirabilis’ meaning wonderful or marvellous.

Lily and her friends were equally transfixed and the desert magic sparkled around them, surprisingly quietening them all, even Buffalo Bill’s melodic tendencies. She wrote: ‘The air was still delightfully fresh and cool, the sun shone brightly from a clear blue sky, Abbie stood glinting in its rays on the track which about half a mile further on joined the “road” back to the sea, and the silence was like a poem of praise for such a heavenly morning . . .’

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT