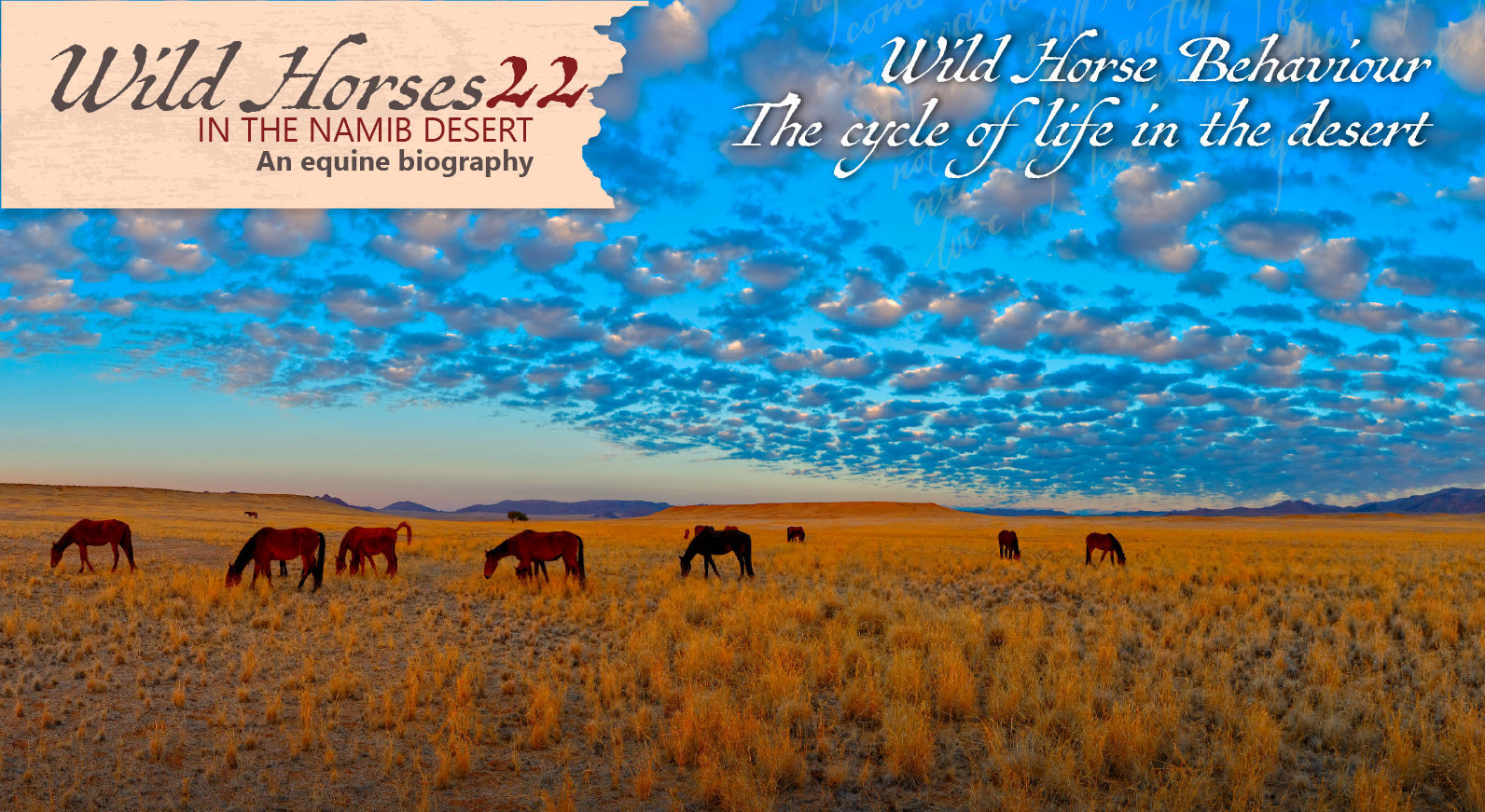

Stories of trade, farming and home life in Great Namaqualand

Set in southern Namibia, Great Namaqualand, ‘Bittersweet Karas Home’ is the story of three families, the Hills, Walsers & Hartungs, whose lives merge and intertwine in a semi-arid land that presents both hardship and blessings. Over the next few months, we would like to share this bittersweet saga with you from the (as yet) unpublished book.

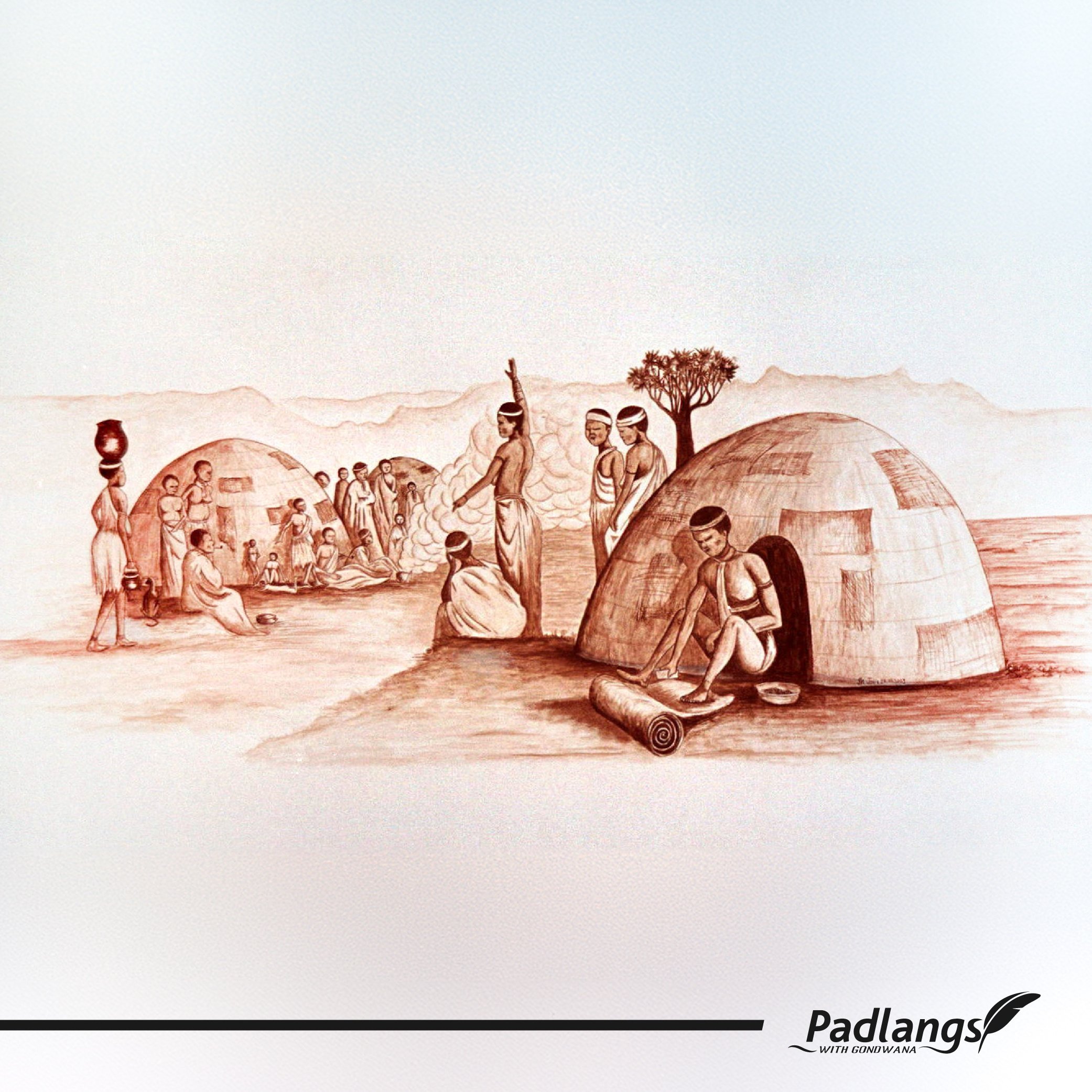

The original inhabitants of the Karas Region were the San and the Khoi or Nama. Then came the Nama-speaking Damara, the Bantu-speakers like the OvaHerero and newcomers such as the Boers or Afrikaners, the British, the Germans, runaway slaves with roots in Madagascar, Indonesia and other Asian countries and white adventurers of almost all European nationalities. The groups have derogatory, praiseworthy as well as neutral names, reflecting a history in which respect was attributed to the in-group and disdain to out-groups. Boer refers to a farming and also a migrant farming (a ‘trekboer’) background and a corresponding lack of urban sophistication; Redneck/’Rooinek’ - to the fact that Brits often suffered from sunburn and that the British soldiers’ pith helmets did not prevent sunburned necks.

In the interface between these groups, new communities developed on the southern side of the Orange River. These were the Basters, whose ancestors were Khoi, settlers and slaves - with African and Asian roots; and the Oorlams - derived from the Malay term ‘orang lama’ and translated as ‘a man of experience’ and the Afrikaans adjective ‘oorlam’ meaning ‘trained’, ‘crafty’, ‘shrewd’ and ‘cunning’ - who had acquired Western skills and Dutch culture, and sometimes were also of mixed descent.

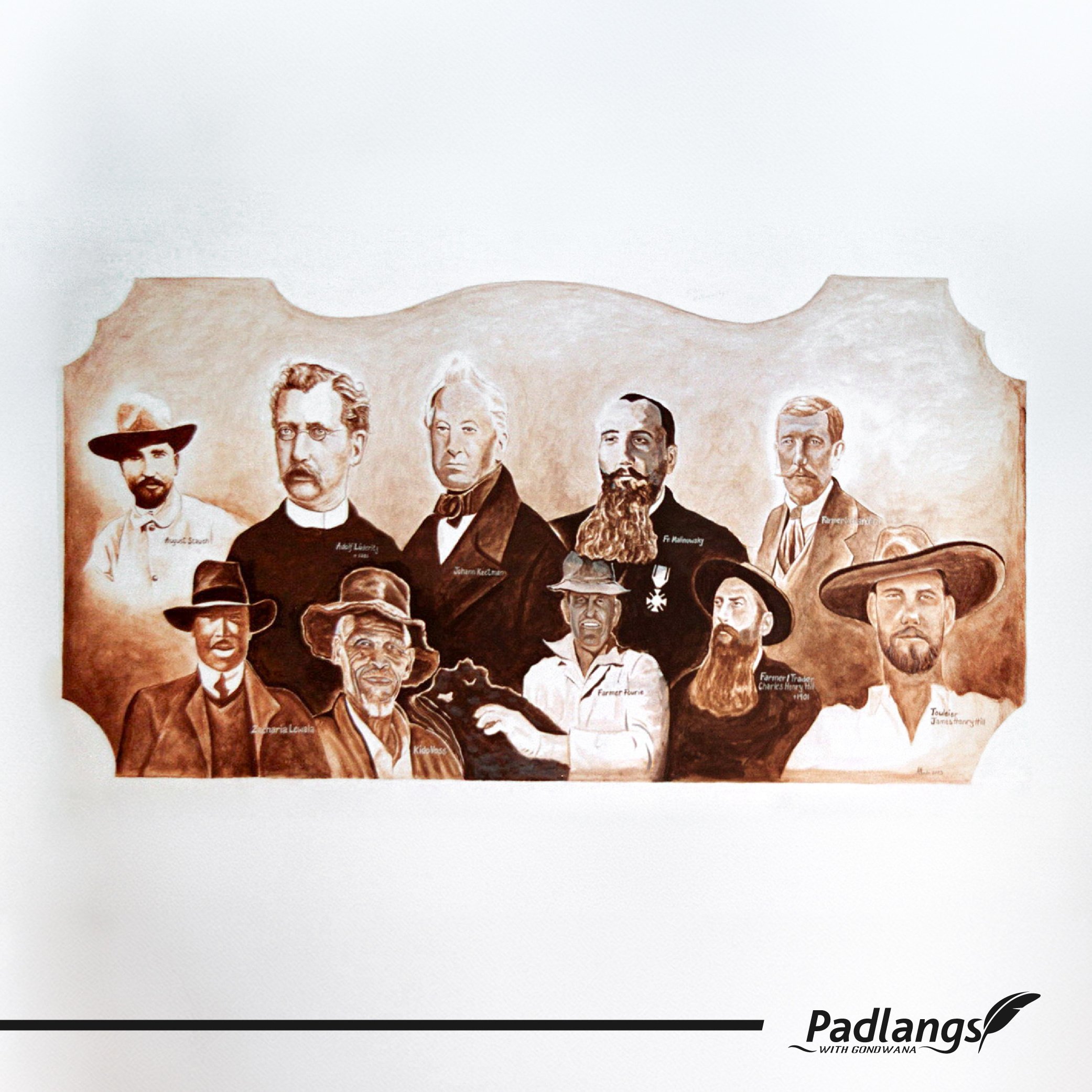

The first group of Europeans crossing the Gariep, Great or Orange River were adventurers and explorers. Jan Bloem arrived at the Cape in 1780 from Thuringia, Germany, ran away from Cape justice when he was accused of theft, became a Kora captain’s scribe and eventually the captain of the Springbok clan of the Kora. He established a dynasty and engaged in a life of cattle rustling that eventually led him, after a botched raid of Tswana cattle, to a poisoned spring where he died. The Swede, Hendrik Wikar, deserted from his employment as a VOC or Dutch East India Company soldier, roamed up and down the Gariep and wrote a book about his explorations that allowed him to return to Cape Town, exonerated.

Adventurers flourished, as did outlaws and conmen. George St Leger Gordon Lennox, aka Scotty Smith, was born in Perth in 1845. Cecil Rhodes commissioned Scotty Smith to form a troop to dismantle Free Town’s illegal diamond trade across the Griqualand border. In 1903, he and Hugo Friedmann offered the German rulers their services as organisers of a mercenary force against Nama rebels, but their offer was ignored because they requested the right for booty. From his farm, Leitland’s Pan, just outside the border of the German colony, Scotty Smith then engaged in spying, gun-running and cattle-rustling against the Germans.

William Leonard Hunt, also known as the Great Farini, who was born in New York in 1838 and grew up in Canada, explored the Kalahari and South Africa, put Zulus and San on the stage in Britain and the United States and created the legend of the Lost City of the Kalahari.

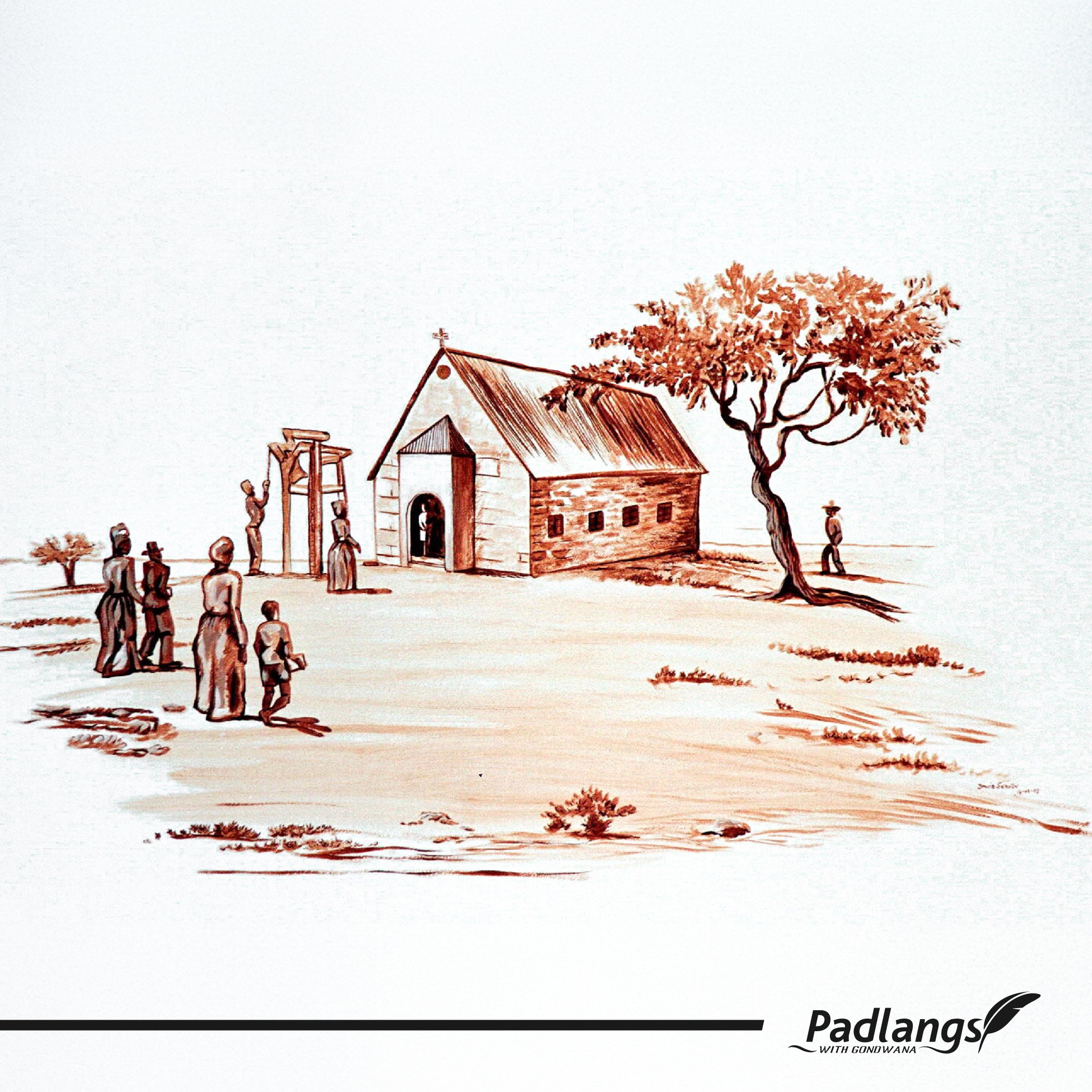

The second wave consisted of traders and missionaries, often invited by Oorlams and Basters whose lifestyles could be boosted by their assistance. Traders and missionaries were vulnerable to theft and violence, not to mention the risk of droughts and diseases. Like their predecessors they formed alliances with indigenous communities. Intermarriage was a way to create amicable bonds with host communities.

Missionaries did not envisage earthly profits and lived humbly. The London Missionary Society campaigned against slavery, believed in a shared universal humanity and expected missionaries to love their congregations. They believed in hard work and frugality but they were also hard taskmasters with no tolerance for honey beer, brandy and dagga consumption, adultery and raiding by their congregations. They sometimes cast themselves in the role of heroes liberating Africans from ‘slavery, sin and ignorance, darkness and paganism’. However ambivalent their attitudes were, they were closer to the indigenous people than other whites. They spoke African languages, shared the everyday life of African communities but also introduced European architecture and town planning at their stations. They practised considerable empathy but were not immune to racist and colonialist ideologies that became more commonplace in late nineteenth century Europe.

Missionaries in South and South West Africa usually came without national baggage and they and their offspring, therefore, often excelled in cultural mediation and innovation. Hans Merensky, son of missionary Alexander Merensky of the Berlin Missionary Society, who taught his son the ‘languages of wind, grass and weathered stones’ using nature as a classroom, advanced geological science and mining in southern Africa. William Philip Schreiner (1857-1919) was prime minister of the Cape Colony from 1898 to 1900 and a liberal champion of African rights. CL Leipoldt and Olive Schreiner (William’s sister) who pioneered southern African literature in English and Afrikaans, had German fathers who worked for the Rhenish and Wesleyan Missionary societies, respectively.

The mission would become a pillar of colonial power and engage in what radical freedom fighters would call mental enslavement, but missionaries also became community builders and contributed to an Africanised Christianity and a theology of liberation.

Takeovers were on the agenda even in the late eighteenth century and came into full swing with the onset of the ‘Scramble for Africa’ and its partition. British traders, hunters and explorers established themselves in South West Africa from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, among them William Coates Palgrave, who led five commissions that paved the way for the annexation to the Cape Colony. Adolf Lüderitz, however, pushed in and bought land in 1883, asked for imperial protection, eventually receiving it and thus initiating a German colony. This happened to the chagrin of the British, who saw this as a ‘predatory move by which [Germany] filched Damaraland and Namaqualand from under the nose of a lethargic British administration’.

Boers had been entering the territory since the eighteenth century and moved into Namibia from the Cape, but, later on, also via Botswana and Angola. Even though there was the short-lived Boer republic, Upingtonia, (1884–1886) in the Grootfontein region under the leadership of William Worthington Jordan, they gained decisive influence only after 1915, when there was a mass immigration of poor Afrikaner farmers from the south.

All these groups interacted, formed alliances, warred against each other and told stories that contained villains and heroes. Who was a villain and who was a hero depended, ultimately, on whoever was telling the story.

(Join us every Sunday to take a step back in time and follow the interesting, sometimes sweet, sometimes heart-wrenching tale.)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT