Their origins steeped in mystery, the wild horses in the Namib Desert have captured imaginations and touched hearts. These resilient animals have survived in the desert for more than a century and over the years have become a major tourist attraction in southern Namibia.

The book ‘Wild Horses in the Namib Desert’ (now out-of-print) is the outcome of a collaboration, revealing the little-known history and behaviour of the wild horse population. Manni Goldbeck sheds light on the horses’ origins, taking the reader back to the tumultuous time of World War l and exploring the more plausible theories, while Telané Greyling (PhD Zoology) shares her knowledge of the intriguing behaviour of the Namib horses gleaned from her many years of research and life amongst the horses. Freelance writer, Ron Swilling, created a text from the material giving it a breath of life. Finally, from the love for the horse and all things wild, the book was born.

An equine biography of the Namib wild horses, the book traces the beginnings of Equus groups on the sub-continent, following their journey over time to Namibia and the present day.

Join us every Sunday as we share the wild horses’ journey with you . . .

(If you’ve missed any of the posts, you can find them on the PadlangsNamibia website.)

𝐂𝐇𝐀𝐏𝐓𝐄𝐑 𝟐 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭 . . .

𝐄𝐦𝐢𝐥 𝐊𝐫𝐞𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐞𝐬𝐚𝐰 𝐨𝐟 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞

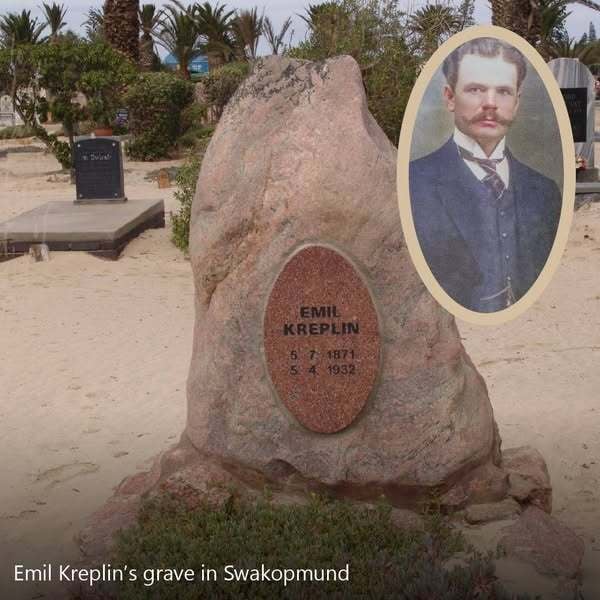

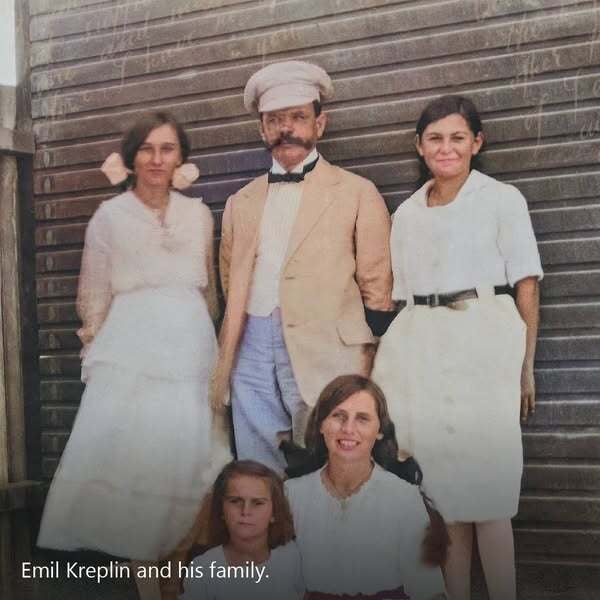

Not many are familiar with the story of Emil Kreplin, who was mayor of Lüderitzbucht from 1909 to 1920. His story, like so many others, is of a man starting with little, becoming extremely wealthy and ending up losing it all in the seesaw of life where it is possible to swing from being poor to rich and back again in the single flash of a lifetime. He was an autocrat, influential and instrumental in much of the social life and advancement of the town. He was also a central figure in the first hours of the diamond rush and the spark that set the area alight with diamond fever. As August Stauch’s superior, he organised the locomotive and accompanied him to Aus to a Dr Peyer, superintendent of the railway hospital who maintained a well-equipped laboratory, for confirmation that the stone found by Lewala was indeed a diamond. He used a portion of his diamond riches to establish a stud farm at Kubub, near Garub, breeding workhorses and racehorses for the fledgling German colony and the surrounding diamond mines.

Kreplin was born in Barth, Pomerania, in Germany, apprenticed to be a blacksmith and joined the military as a professional soldier. He travelled with the Schutztruppe to German South West Africa in 1894 and was involved in the first fighting in the German colony against the Nama people. After twelve years in the service, he returned to Germany. The country had entered his heart however, and he soon returned to work for a railway construction company, Lenz & Co, as an ‘Oberbahnmeister’ (a railway supervisor). He was therefore at the right place at the right time when the momentous discovery of diamonds enabled men like him and Stauch to become remarkably wealthy almost overnight. He was one of the founders of Charlottental Diamantengesellschaft in 1908 and later on became the director of Kolmanskop Diamond Mines Ltd.

Emil Kreplin was such a prominent figure in Lüderitzbucht that it is recorded ‘he practically controlled the place’. He played a crucial part in the negotiations with the German troops before they evacuated the town at the beginning of the South West Africa Campaign, convincing them to leave Lüderitzbucht intact. He was interned in the Union of South Africa when the Union forces arrived for the duration of the campaign, afterwards resuming his life in Lüderitzbucht. He returned to Germany in 1920 for a ten-year period, hoping to return to South West Africa at a future time, and visited some years later in 1925. He told the local newspaper and townspeople who welcomed him on his return, “It is good to breathe African air and spirit again, from the outer as well as the inner.” Kolmanskop Diamond Mines Ltd was placed in voluntary liquidation in 1923.

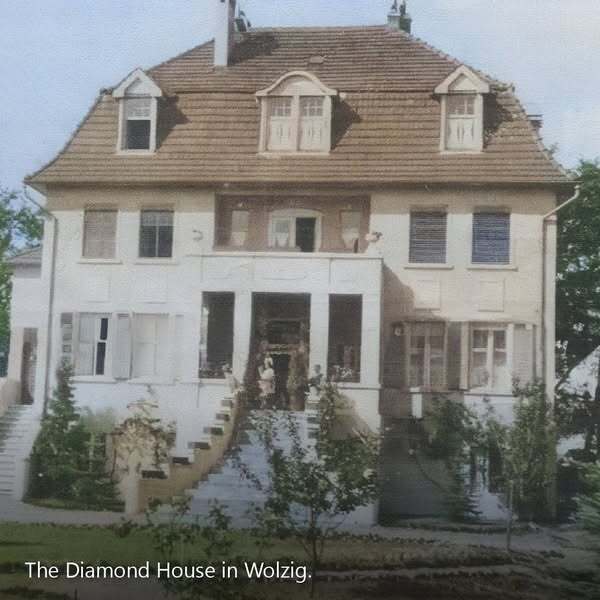

In Germany, Kreplin lived in a grand house in the rural town of Wolzig on the outskirts of Berlin, bought with his diamond riches and appropriately referred to as ‘Haus Lüderitzbucht’ (Lüderitz Bay House), known by locals simply as ‘The Diamond House’. But he was unable to keep it through the depression years.

He returned to South West Africa where he bought a plot in Omaruru and started farming. In 1932 there was unusually heavy rainfall in the area and the Omaruru River came down in flood, taking his livelihood and last remaining pennies with it in its rush to the sea. Kreplin had finally lost everything. He went to Swakopmund to ask help from friends, and feeling abandoned and hopeless wrote a ‘farewell forever’ letter to his daughter Fritzi and shot himself in the heart on the banks of the Swakop River.

.png)

.png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT