Set in southern Namibia, Great Namaqualand, ‘Bittersweet Karas Home’ is the story of three families, the Hills, Walsers & Hartungs, whose lives merge and intertwine in a semi-arid land that presents both hardship and blessings. Over the next few months, we would like to share this bittersweet saga with you from the (as yet) unpublished book.

CHAPTER ONE (cont . . .)

The second generation

Susanna Rosina Hill quickly adjusted to the new environment. Many people in the area had known her father and welcomed the couple and their children: Donald Duncan, James Henry, Roland Martin and Charles John; and Agnes, Elizabeth, Wilhelmina Charlotte and Margaret Susan.

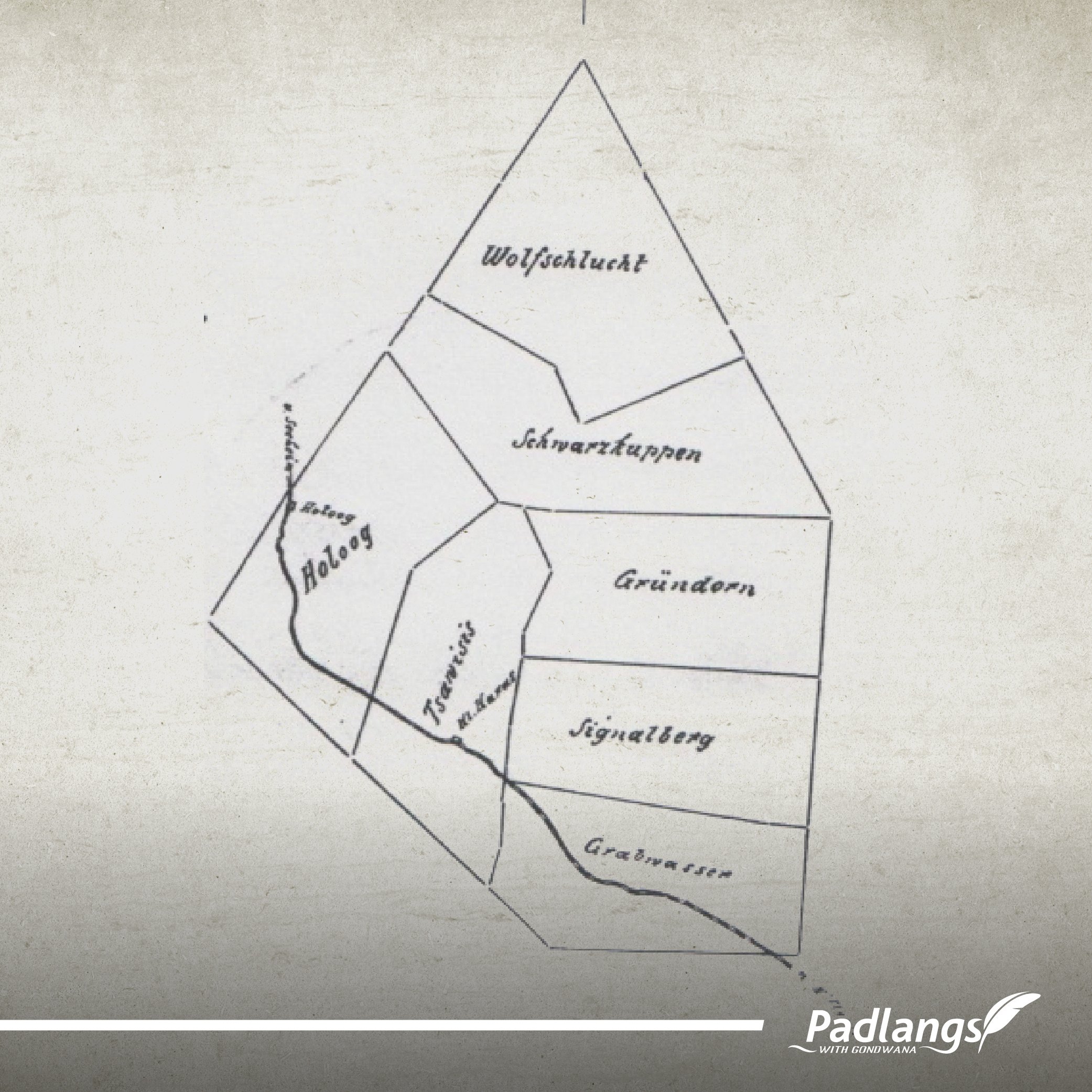

Susanna watched the farm grow and although she enjoyed the vast farmland of Wolfsschlucht, Groendoorn, Tsawisis, Holoog, Signalberg and Grabwasser that had become her home, she also enjoyed her visits back to Steinkopf and to Cape Town.

She raised her children, seeing them acquire pastoralist and hunting skills, and learning the Nama language from the everyday interaction with their Nama playmates, the way she had learned it. She educated her own children and hired private tutors when necessary. The girls furthered their studies at boarding schools in England and at the Cape.

Charles Henry Hill kept in contact with the 1820 settler community and his relatives in the Eastern Cape. Nieces and nephews came for extended visits by ox-wagon, enjoying the adventure of living and working with their cousins on the farm, while the Hills visited their relatives in the Cape on journeys that would often take months to complete.

At the mercy of external influences

Up until 1902, the number of German Schutztruppe in the south-western corner of Africa remained small at about 700. Chartered companies were expected to provide the input for the colonial venture, with the German state only offering basic support. As German private business was sluggish, there was not much progress and state and business were locked in a waiting game.

By 1886, Adolf Lüderitz had spent all of his and his wife’s money and was bankrupt. He became preoccupied with a search for gold and diamonds, hoping to solve his money problem. He engaged in a mineralogical exploration of the Orange River starting at the eastern border. On 30 October 1886 he reached the estuary and the end of his fruitless journey and faced a long, slow overland journey back to Lüderitzbucht by ox-wagon. Rather than undertaking the journey by land and using the canvas boat that had carried him downriver, he (and his helmsman) set sail for Lüderitzbucht with the hope of a discovery along the coast.

According to sources, ‘The helmsman [Steingröver] initially refused because he knew that facing the open sea in a feeble canvas boat was a foolhardy plan and meant certain death. Onlookers were able to detect the boat on the top of breakers three times, then it failed to re-emerge and neither Lüderitz nor the helmsman were ever seen again. The whole coast was scoured on land and on sea, but nothing was ever found. Thus ended the man who gave Germany her South West African colony.

Whether Lüderitz perished in the cold Atlantic Ocean or in the Namib prospecting for diamonds, remains a mystery. The bitter irony is that the ground outside his Lüderitzbucht warehouse was found to be awash with diamonds only twenty years later.

Gold fever erupted and fizzled out just as quickly in 1887. Australian diggers played a leading role, feeding the frenzy by salting samples with gold. The gold bubble burst when Berlin geologists found that the samples Governor Göring had submitted were fakes. Göring was suspected of complicity in fraud. He encountered further humiliation on 30 October 1888 when the Herero chief, Maherero, and his English advisor, Robert Lewis, told him in no uncertain terms that they rejected German rule. He fled to the safety of British Walvis Bay and then to Cape Town. Ironically, he travelled in the wagon bought from Palgrave. ‘This wagon had tossed around the emissaries of two European governments in the same fashion; they had not made a difference, and now it survived both of them.’

In the first decade, traders like Hill and Duncan continually discussed the German rule because it affected their lives and livelihood. The Schutztruppe were too weak to offer real protection but neither could they do much harm. The German colony was certainly not an economic success story, with German commoners financing government expenses with their taxes. It also did not attract many settlers because few had the capital needed to start a business and jobs were scarce.

Change arrived in the 1890s with Kaiser Wilhelm II. The previous outcome-centred Realpolitik was replaced by Weltpolitik, a policy seeking ‘a place in the sun’ for Germany that would equal its industrial progress, primarily with an empire and a fleet rivalling the British one. The Kaiser was prepared to spend rivers of the nation’s gold as long as it was for national prestige. In the same year, the Anglo-German Agreement signalled Britain’s final acceptance of the annexation and compelled the Bondelswarts leaders to sign a protective treaty with the new government. The Hills and the Duncans adopted different strategies to deal with the changes.

This also meant that all the purchases and hire purchases by the Bondelswarts were reassessed by German courts, bringing their past transactions under scrutiny. Charles Henry Hill’s son-in-law, Carl Wilhelm Walser, had signed a contract for the land of Ukamas and Arris, which was now torn up. According to the German court, Ukamas was not Bondelswarts but Afrikaner Oorlam land and had become German Crown land after the Oorlam rebellion of 1897. Carl Wilhelm Walser, therefore, would have to buy this land from the government for 20 000 Reichsmark. Emil Hartung also lost Arris, which he had leased from Walser. This land had become part of British Bechuanaland and the British denied that the Bondelswarts had any land rights there. The Bondelswarts-Hill contract was still generally accepted in 1894 but in 1908 administrators like Hintrager doubted that the Hills case would be judged in a white court because Susanna Rosina Wimmer and her descendants had been classified as ‘natives’. The Hills had sufficient support in Namaqualand’s German administration to have this assessment brushed aside. In the less favourable climate, the court now questioned the size of the Groendoorn farm complex in relation to the money paid for it. When German rule ended in 1915, the case was still dragging on. There was tentative confirmation for the whole territory because the Hills had influential supporters, namely, former District Chief von Kageneck, the missionaries and the Bondelswarts leader. (The South African administration would reopen the court case after the war.) The final confirmation of the 1876 contract came when the Hills were already losing economic control of the land. The Duncans were spared this never-ending legal struggle, having previously sold their share to the Hills.

In 1902 there were 2 595 Germans, 1 354 Boers and 452 British citizens in German South West Africa. In an estimated total population of 200 000, whites of whatever nationality were a tiny minority, but in the settler community the British were far from insignificant. In spite of their low numbers, they wielded considerable economic power backed by the economic powerhouse of the Cape and diamond-rich Kimberley. Cecil Rhodes bought up a number of German societies, often staffing them with German managers who were in his employ, thus safeguarding his economic interests.

Rhodes also used undercover strategies. In German South West Africa he made use of George St Leger Lennox, better known as Scotty Smith, who was engaged in raiding, trading and spying in the German colony from his farm Leitland’s Pan at the British Bechuanaland-South West African border. Rhodes was the director of the Great Namaqualand Exploration Company. Robert Duncan, Robert McKimmie (Duncan’s Kimberley-based son-in-law) and their partners, Spangenberg, Alcock and Halliburton, were members of this company. Contrary to what its name suggests, one of its main aims was to supply the Witboois with arms and ammunition to fight the new government. Robert Duncan actively supported British (and Witbooi) policies.

The Germans accused Duncan and his associates of high treason for selling guns to the Witboois at the time of the 1894 Naukluft Campaign. They surrendered to the authorities and were imprisoned. Their families expected to be expelled from the country and to lose all their property.

As the Duncan & Hill Company had dissolved in 1888, the Hills were not involved with Duncan’s activities and were not exposed to any legal restrictions. It was safer to keep a low profile even if sympathetic to the Duncans.

After their victory in the Naukluft battle, Governor Leutwein and Von Burgsdorff decided that it was far more advantageous for them not to crush the Witboois. They allowed them limited autonomy in exchange for military support to the Schutztruppe and a protection treaty. The Duncan men were treated like the Witboois and acquitted. After his release, Robert Duncan and his family cooperated with the Germans. Some of his daughters would even marry German farmers. Robert Duncan junior assisted Schutztruppe soldiers and was eventually killed by a guerrilla group under Captain Simon Koper in 1908. Non-German traders realised that they had lost out to the German authorities but still hoped for more promising future changes.

(Join us every Sunday to take a step back in time and follow the interesting, sometimes sweet, sometimes heart-wrenching tale.)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT