The book ‘Wild Horses in the Namib Desert’ (now out-of-print) is the outcome of a collaboration, revealing the little-known history and behaviour of the wild horse population. Manni Goldbeck sheds light on the horses’ origins, taking the reader back to the tumultuous time of World War l and exploring the more plausible theories, while Telané Greyling (PhD Zoology) shares her knowledge of the intriguing behaviour of the Namib horses gleaned from her many years of research and life amongst the horses. Freelance writer, Ron Swilling, created a text from the material giving it a breath of life. Finally, from the love for the horse and all things wild, the book was born.

An equine biography of the Namib wild horses, the book traces the beginnings of Equus groups on the sub-continent, following their journey over time to Namibia and the present day.

Join us every Sunday as we share the wild horses’ journey with you . . .

(If you’ve missed any of the posts, you can find them on the PadlangsNamibia website.)

𝐂𝐇𝐀𝐏𝐓𝐄𝐑 𝟐 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭 . . .

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐮𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝟏𝟗𝟏𝟓 𝐢𝐧 𝐆𝐚𝐫𝐮𝐛

‘. . . If your ministers at the same time desire and feel themselves able to seize such part of German South West Africa as will give them command of Swakopmund, Lüderitzbucht and the wireless stations there or in the interior, we should feel that this was a great and urgent Imperial service.’

(From British Government cable to Prime Minister Louis Botha of the Union of South Africa, 6 August 1914)

Champagne corks popped, spectators dressed in their European finery (women’s hats adorned with ostrich feathers) clapped as imported race horses surged to the winning post. Lüderitzbucht was bathed in diamond glory. Elaborate German-style houses lined the streets, bars flourished and the Kapps Hotel saw more visitors than the local church. People bought champagne by the crate rather than by the bottle and men are said to have toasted by sipping the sparkling wine out of ladies’ shoes. Horse racing was the social event of the new elite and important racing events often coincided with the arrival of a ship in the bay. When Emil Kreplin celebrated his 43rd birthday on 5 July 1914, he was at the highpoint in his career, a respected mayor of the town, often a master of ceremonies, owning and breeding the best race and work horses, and was rich with diamond wealth. Little did he know that the clouds of war were massing on the horizon, that war would break out a month later in Europe and during the following month Union troops would descend on the desert diamond town irrevocably altering destinies in their wake.

.jpg?width=600&height=600&name=508770517_1114125957404778_5527224637472265769_n%20(1).jpg)

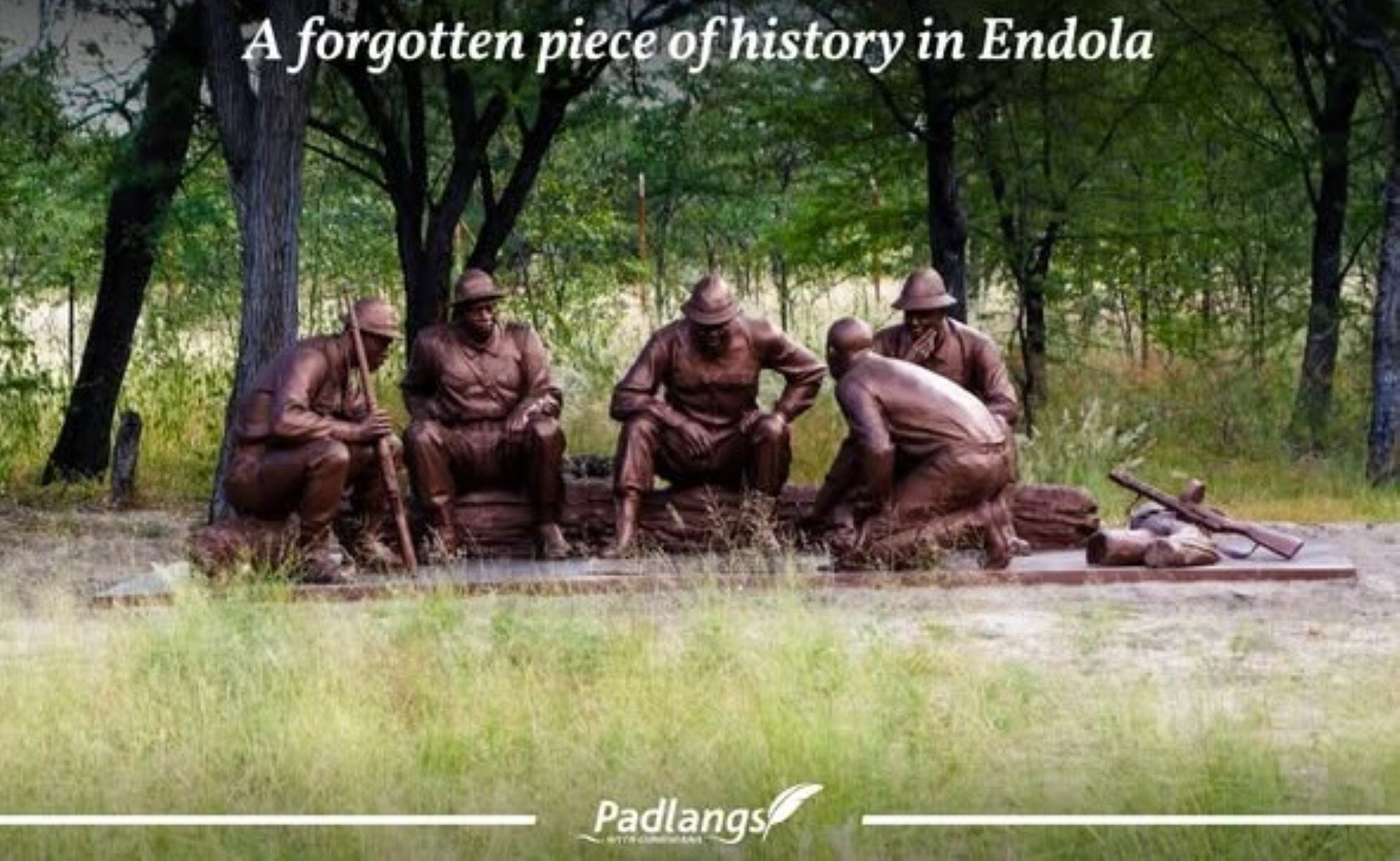

The Imperial invitation extended to the Union of South Africa to seize German South West Africa was ‘cordially agreed’ upon by General Botha and his colleagues. On 19 September 1914, when the Union forces landed at Lüderitzbucht, the German troops had already retreated inland blowing up the railway line behind them. When the Union forces’ Captain De Meillon, head of reconnaissance, arrived with his advance party and entered a deserted house, they found hot coffee still standing on the dining-room table and the bed still warm. The troops landed the following day in the town they described as an ‘unpleasing place, bare of everything in the way of natural growth’. They hastily replaced the white flag raised above the town hall with the Union Jack. It was soon decided to send the remaining civilian occupants of Lüderitzbucht (not surprisingly referred to as ‘obstreperous’ and ‘cool’ by the invading troops) to the Union for internment, Bürgermeister (mayor) Kreplin included. Although the original plan was for the Union forces to close in on German South West Africa from three different directions, the advance was suspended as a result of the rebellion in South Africa in protest against the invasion. No other forces entered the country until the end of the year when the rebellion had been quelled. While troops stationed outside the town camped in the desert and worked under harsh conditions, battling the elements and repairing railway tracks and bridges, the Lüderitzbucht garrison made itself at home enjoying the comforts established by the German founders of the town. During the campaign some of the streets would be renamed, and the main thoroughfare Bismarck Strasse would become fondly known as King George Street.

After several months in the town, the days of gramophones and German music abruptly ended. The campaign was resumed and Union forces followed the German soldiers into the interior, inching forward, continually repairing the railway line, a lifeline in the desert ensuring the continuity of supplies from Lüderitzbucht. The rate of advance was limited by the shortage of water. Every drop of water required during the advance to Garub, 101 kilometres east, had to be condensed from sea water at the coast or transported by ship from the Cape. The largest transport vessel in the campaign, the SS Monarch, carried 4 000 horses, tons of fodder, supplies and 750 000 gallons of Table Mountain water. Progress was extremely slow as the men battled the wind and heat, crossed deep sand and jagged rocks. One account succinctly describes the desolate terrain: ‘The long treks across this God-forsaken country are like a hideous nightmare … The country now is simply rock and sand, rock and sand… A few horses give in occasionally’. The water from a few isolated wells, the desalination plant and the transport ships was not sufficient for all the men, horses and mules. The Namib Desert was aptly known as the ‘Thirstland’ and with little action seen by the troops apart from the odd skirmish, the real enemy was the desert. The Germans had realised the strategic value of water and the railway in the desert conditions, which they considered ‘their strongest defence’. As they were hopelessly outnumbered, approximately 6 000 soldiers against 50 000 Union soldiers, they could only put up resistance where possible, lay mines and destroy railway infrastructure and boreholes to buy time and delay the inevitable. They poisoned wells and waterholes, either by throwing in a dead animal, animal entrails, carbolic acid, creosote or sheep dip. When Union troops reached an abandoned settlement, they had to first test the water from the wells for poison and had to repair boreholes before they could gain access to the life-giving fluid.

When the Union forces reached Garub on 22 February 1915, more than two months later, they found that the water tanks had been demolished, the station house had been torched and the railway to the east had been dynamited. The soldiers shouted through parched lips as they arrived, “Water, water.” A trooper aptly reported about life in the desert: ‘We breathed sand, we chewed it, we took it in our food, literally – there was sand in the sugar; we thought sand, we dreamed it’. The boreholes were repaired and re-drilled, and the underground supply of potable water ensured that the 10 000 men and 6 000 animals were well-watered. The area around the boreholes was pounded into a fine powder that rose in an enormous dust-cloud as the animals in their thousands gathered to drink.

It was decided to build a narrow-gauge railway loop from the station house to the boreholes to be able to fill the water trains. The four-and-a-half-kilometre deviation turned out to be one of the most expensive strips of railway ever built, costing £75 000 per mile, taking into account the time utilised and the cost of Union soldiers. It took nearly a month to complete, delaying the advance, and while it was under construction thousands of men with their animals stood idly by.

The German troops were stationed in the hills at Aus, 25 kilometres to the east. With an airfield, wireless masts, an intricate system of trenches and fortifications that ran through the hills, look- out posts and gun emplacements, they were well placed for defence and prepared to make a strong stand. They had just one aircraft, which flew before sunrise when it was easier to take off in the relative coolness of the morning. The German airman was affectionately referred to by the Union troops as ‘Fritz’, and after sighting him in the morning they knew they would be safe from air attack for the remainder of the day.

Fritz paid several visits to the Union base at Garub but only bombed it three times, the last being on 27 March, the summer of 1915, to mask the Germans’ retreat, scattering about 1 700 grazing cavalry horses and causing considerable havoc. When the Union forces from Garub reached Aus three days later, the German troops had already evacuated to the north to avoid being cornered by advancing Union forces fast closing in on them from the east and the south. Under the circumstances, they ‘had no option but to abandon their fine fortifications’. The Union forces were therefore fortunate to avoid a hard fight and the small town of Aus narrowly escaped becoming one of the main battlefields in the campaign. The strategic importance of Aus and the expectation of fierce resistance was epitomised by a soldier’s report: ‘Aus had always been a name to conjure with right from the time we had set foot in Lüderitzbucht’. After securing the water sources, they followed the Germans, hot on their heels.

The two forces eventually engaged at Gibeon bringing the southern part of the campaign to a close. The Germans surrendered on 9 July 1915 at Khorab, north-east of Otavi in northern Namibia, after several rounds of peace talks. German South West Africa fell under the Union of South Africa military administration until it was mandated to the Union by the League of Nations after the war. The southern African ‘side-show’ to the European war, which was still to continue for several more years, was over. In the proceeding weeks of evacuation, the area saw much traffic as troops, equipment and animals were transported back to Lüderitzbucht and the Union. Interned civilians from the Union and reservists from Khorab were allowed to return to their homes. A Prisoner-of-War camp was constructed on the plains east of Aus, housing 1 552 Schutztruppe soldiers. It was at this time of epic pandemonium that the horses, which had been abandoned during the war period and in the ensuing chaos, began to congregate at Garub.

Kreplin returned from his internment in the Cape in 1915 and resumed his life and duties in Lüderitzbucht. In 1920 he returned to Germany for health and personal reasons, following many of his countrymen who had left or been deported at the end of the war. His farewell party took place in the Kapps Hotel hall with many diamond magnates, including the renowned August Stauch, present. In gratitude for the years of service he generously gave the town, he was awarded honorary citizenship. He departed by rail to Cape Town and was set to sail via Holland to Germany. The entire town assembled to shake hands with him and wish him well as he boarded the train, with many a ‘Hurrah, hurrah’ trailing after him in farewell as the train steamed off into the desert.

.png)

.png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT