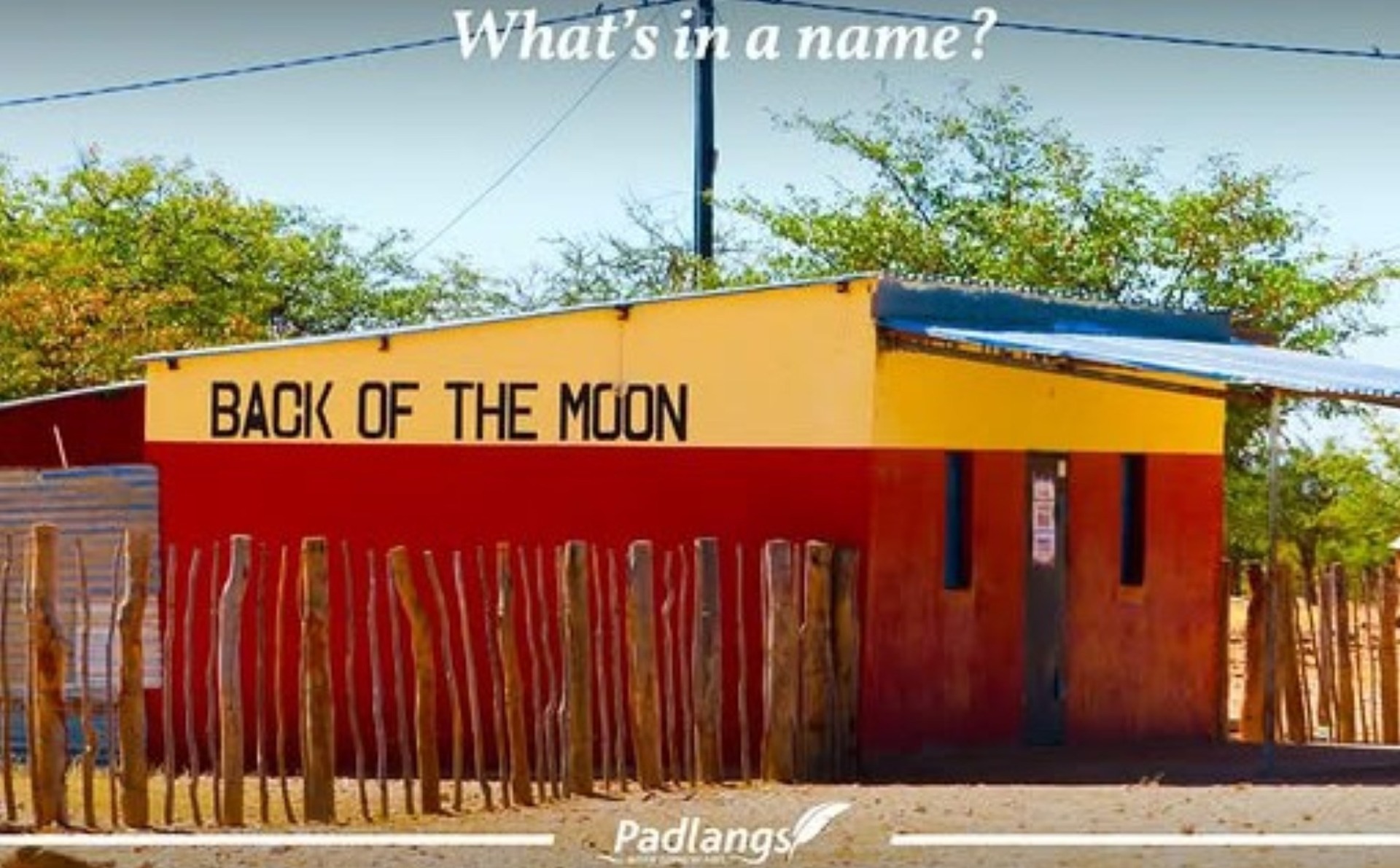

When I’m driving around Namibia, I’m always intrigued by the farm names I come across. The meanings of some are obvious like ‘Rustenvrede’ and ‘Vergenoeg’ describing the owners’ relief and joy at finally settling down. Others like ‘Brakwater’ or ‘Lekkerwater’ bring to mind the challenge of finding a reliable source of water in the semi-arid land. But, there are some names like ‘Nuremberg’ and ‘Aspro’ near Outjo that had me completely puzzled until I found an old article in the Windhoek Observer from 1 November 2003, written by Wim Botha.

The arbitrary farm names made more sense after reading it – that is if sense even comes into it. Rather than there being any heartfelt emotion involved in the name-giving, it was more a matter of assigning a myriad of names in a short time, as a formality more than anything else. And the surveyor simply ran out of ideas – or imagination.

Residents in the Outjo area would have been aware of farms bearing the unlikely names from World War Two, like Jannie (named after Smuts), Stalingrad (named after the Russian city that bore Joseph Stalin’s name) and Nuremberg (named after the city where the Nuremberg trials were held after WWII). Regardless of political inclination, the farm names, like most things in life that become familiar over time, lost any associated meaning and simply just became names. Most of these names were changed over the years, a few have remained and some have reverted back to their original Nama, Damara and Otjiherero names.

The series of strange names in northern Namibia began when Imperial Cold Storage, one of the largest meat processing companies in southern Africa, discovered that a consignment of quality meat they received originated from north-east of Outjo. The company purchased approximately 100 000 hectares in the area for farming purposes. During the war, it reduced its holdings and sold off some properties to karakul millionaire, Ernst Luchtenstein. The land, estimated to be 40 000 to 50 000 hectares, was to be divided into 34 farms and Professor GA Watermeyer, a retired professor from the University of the Witwatersrand, was assigned the task of surveying the land.

At the time, it was a requirement when registering land to provide not only precise measurements of the perimeters, but also a farm name and number. One would guess that after running out of names (and possibly suffering the effects of working under the blazing Namibian sun) and with nothing obvious in the topography to distinguish one farm from the other, that Watermeyer simply resorted to describing his own condition. Three farms along the Ugab River amusingly indicated this. They bore the names ‘Aspro’, ‘Okay’ and ‘Haastig’. As the story goes (and apologies to the late professor as it may be pure fabrication), Watermeyer took an aspirin for his headache at the farm he named ‘Aspro’, the next day when he surveyed the adjacent farm he was ‘Okay’ and by the third day he was in a hurry (‘Haastig’) to finish his work. The farm names ‘Aspro’ and ‘Okay’ still exist today, but ‘Haastig’ has been renamed.

And as for the farm names from the world war, well it seems that that there were too many farms for the limited number of generals, world leaders and politicians, so Watermeyer also used some of their nicknames – and those of their spouses – like ‘Jannie’ and ‘Oubaas’ for Jan Smuts and ‘Issie’ and ‘Ouma’ for his wife.

In the article, journalist Wim Botha wondered why someone like Churchill didn’t feature among the names. We can only guess that it was personal.

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT