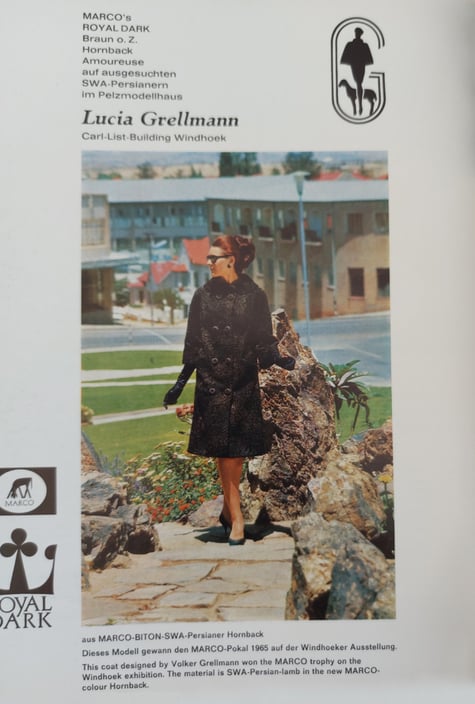

The fur shop started small in 1952, in the aftermath of World War II, at the home of Lucia and Heiner Grellmann. More than a decade later, Lucia would open her fur shop in the Car List building in Windhoek with her son Volker. It was the first fur shop in the country, the second in southern Africa, and would in time become part of the large worldwide fashion industry.

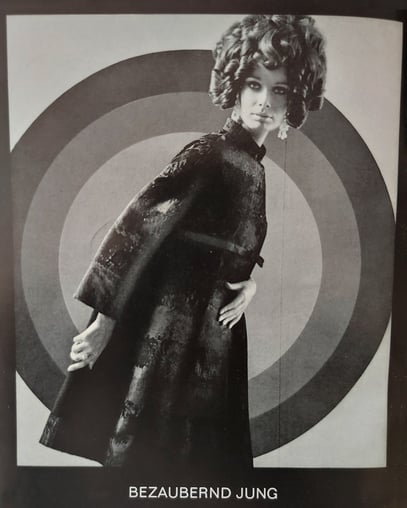

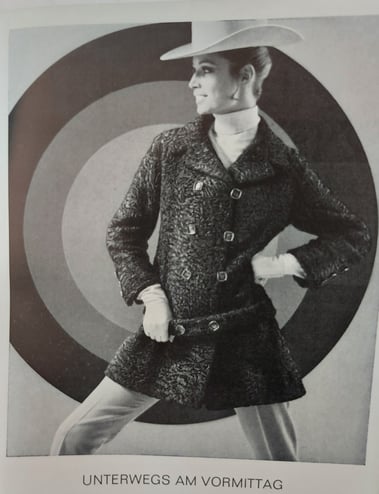

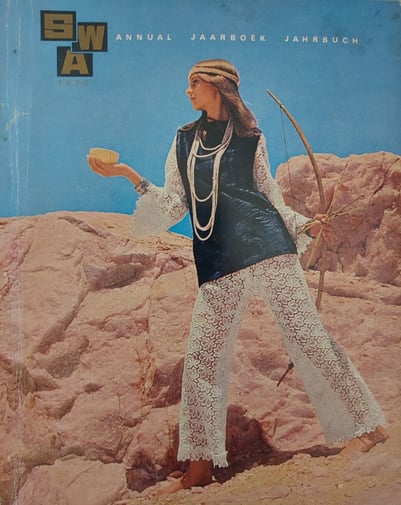

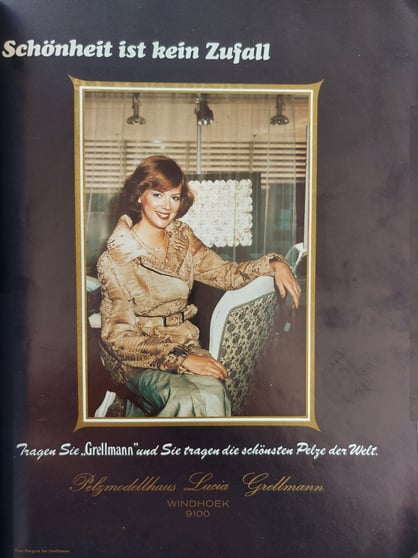

I had always noticed the full-page advertisements in the old SWA annuals published by Sam Davis with the lanky models posing elegantly in karakul furs. Over the years I had researched the history of karakul farming in Namibia (then South West Africa), but had never touched on the furriers, the fur shops or the marketing of karakul garments in the country. Fifty years after those early adverts, I had the opportunity to meet up with Anke Grellmann, Lucia’s daughter-in-law, who played a pivotal role in karakul fashion and was able to fill in those missing chapters.

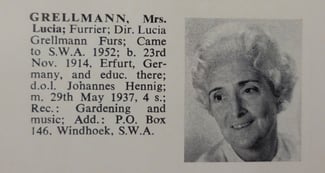

Over coffee and biscuits on her farm in central Namibia she told me how the destiny of two families, the Grellmanns and the Hinsches, were intertwined from the 1950s when they both left Germany after the war and boarded ships to southern Africa. The first was the Grellmann family, who hailed from Erfurt in eastern Germany where Lucia’s parents had a fur shop. After their house was taken away from them, they fled to West Germany. After two years in Stuttgart, Lucia boarded a ship to Cape Town with her husband Heiner, who had spent many years in a prisoner-of-war camp, and their four children – Hans Werner, Volker, Wolfie and Peter. The Grellmanns docked in Walvis Bay in 1952. A year later, in February 1953, the Hinsch family arrived in Cape Town and took the train northwards to South West Africa. Anke was eight years old at the time.

Lucia was well-versed in fur. She had, after all, started working for her parents at the tender age of fourteen and had experience in the fur business. The war years had brought hardship and suffering to the family. Lucia’s fur shop had humble beginnings, but grew quickly over the years.

Her second-oldest son, Volker, was destined to follow in her footsteps, but when the families arrived in the country and met, he was just ten-years old, two years older than Anke. When Volker finished school, he trained as a furrier (Kürschner) in Fuerstenfeldbruck, Germany. On his return, mother and son moved the home business to the shop in central Windhoek with a workshop below and showroom above. Volker and Anke had remained good friends over the years and eventually in 1966, when she was twenty-one and he was twenty-three, they married.

The couple brought a fresh, younger energy to Grellmann Furs and started marketing their coats. Karakul had become synonymous with South West Africa and drew attention to the country. Anke started to train models for fashion photography, organising photography shoots in striking outdoor locations, including the desert and on cheetah farms. Many new styles in fur fashion, like the Zhivago and Safari look, were introduced by Lucia Grellmann Furs. Although many of the beautiful women who appeared on the pages of the SWA annuals weren’t professional models, supermodels like Veruschka von Lehndorff modelled furs from Lucia Grellmann Furs and well-known fashion houses like Belmaine for the popular fashion magazine, Vogue. Representatives from large fashion houses in Germany came to visit the country and as karakul fashion grew worldwide, Swakara – South West Africa Karakul, the country’s ‘black diamond’, became increasingly popular.

In the early 1970s, Lucia felt it time to retire from the fur industry and Volker and Anke moved into the safari business and concentrated on Anvo hunting safaris, introducing ‘conservation through selective hunting’. (Anvo’s story will be posted at a later date.)

The Grellmanns had closed the shop in the nick of time. By the mid-1980s the karakul market had crashed as the result of a change in fashion, a series of droughts and pressure from animal anti-cruelty movements. The fur shop became a snapshot in time and the many advertisements of the karakul models in the old SWA annuals, reminders of a glamorous past. Although Swakara continues today, it is a fraction of the once lucrative business it was in its heyday.

in the 60s, 70s and 80s, Swakara and its marketing had a huge impact on the fledgeling tourism industry, putting the country on the map.

.png)

.png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT