The romance of the Skeleton Coast’s stormy seas, shipwrecks and seafaring tales make exploring this forbidding and notorious Namibian coastline an intriguing adventure. And if you only find a shipwreck or two, rusting away in the salty water or on the desert shore, don’t despair, there are many more treasures to dazzle and enchant on the route from Swakopmund northwards to the swaying makalani palms of Palmwag.

The route always elicits excitement for its unusual attractions, the untold surprises of a desert country. And no matter how many times I drive it, I always find myself smiling and looking forward to the out-of-the-ordinary extraordinary day.

A hundred-and thirty kilometres north of Swakopmund is the Cape Cross Seal Reserve. It’s a bustling colony of Cape fur seals, a cacophony of sound and commotion, as they bark at each other, call for their mothers or make their way into the sea, already brimming with shiny seals. Their quieter side is revealed on closer inspection as they curl into each other with an underwater malleability and dog-like beauty, opening soft, big eyes before drifting off to sleep.

But Cape Cross shouldn’t be left without acknowledging its history as one of the places where intrepid Portuguese navigator, Diego Cão, erected a cross (padrão) in 1486 on his second trip down the African coast in search of a route to the East, calling it ‘Cabo do Padrão’. Four hundred years later it would be the site of the Damaraland Guano Company, which harvested seals and guano deposits (considered ‘white gold’) as a fertiliser for the European market. The small settlement had a post-office, police station and customs office, and boasts the first postal robbery. It was short-lived and in 1903, after only nine years of production, the rocks had already been scraped bare and the seal population had started to dwindle. Replicas of the Portuguese crosses remain, as does a small graveyard at the entrance to the reserve and the strip of rusty old railway line that is sometime visible in the sand.

As I continued northwards with a now lingering seal odour clinging to my hair and clothes, I passed brown hyena caution signs and more salt tables that lined the road, as well as the signs to fishing holes which pepper the route right up to the gates of the Skeleton Coast Park. These mark fishing spots, some with the old Mile signs (denoting the distance from Swakopmund) and the others with quirky names that have been given by locals to remember a good fishing hole. They include ‘Sarah se gat’, named after a legendary fisherwoman, Sarah de Jager (singer Carike Keuzenkamp even wrote a song about her), ‘Bennie se rooi lorrie’ (as the story goes, poor Bennie must have left his toy truck on the beach), ‘Baklei (Argument) Gat’ (and who knows what happened there), ‘Horingbaai’ (with its collection of horns placed around a post) and more recent ones like ‘Snoffels se gat’, remembering a beloved dog. Every time I drive the route, I spot a new one and this time I spotted two newies: ‘Meerkat Gat’ and ‘Skoonpa (Father-in-law) se gat’.

I felt like I was deep in the territory when I passed St Nowhere camp, Mile 108 and reached the southern entrance to the Skeleton Coast Park, Ugab Gate, with its whale bones and, the ominous skull-and-crossbones graphic that still adorns the gate that ushers you into the park with a bit of trepidation. The road leads through the stark landscape 143km northwards to Springbokwasser gate. It’s a quiet desert world here, no longer punctuated by fishing spots and the occasional fishing vehicle with rods jutting out like radio antennae searching for life elsewhere.

Once you’ve negotiated the cracked mud and bumpy road from the Ugab and Huab rivers searching for the sea after a good rainy season, you are surrounded by the gravel planes, sandy hills, coated with a magnetite frosting, and a tapestry of earthy colours. There is little else except the remnants from the Toscanini mine and the old oil rig with delicate rusty edges like filigree. But first the wreck of the South West Seal, sixteen kilometres north of the Ugab Gate. This is a stop not to be missed. The South African fishing vessel was wrecked here in 1976 when a fire broke out on board. Today, the remains lie peeping out of the sand on the shoreline, playing with the waves.

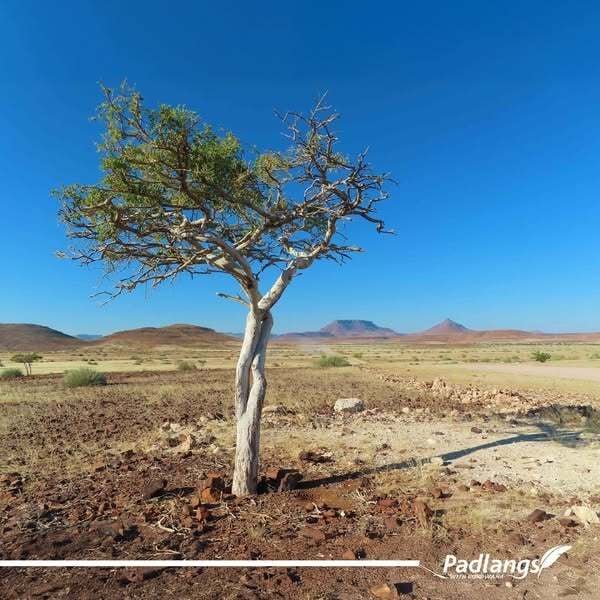

In case you think that the intrigue is done when you veer eastwards towards the Springbokwasser gate and Khorixas, think again. Some of it is just beginning. The ‘Red line’ veterinary cordon fence, preventing the spread of animal diseases like Foot and Mouth, flanks one side of the road and on the other are fields of welwitschia, the wonderful and miraculous two-leaved desert plants. The green of the Huab Valley appears and in the distance the red tabletop Etendeka mountains that characterise this area of Damaraland.

When I popped out of the park at Springbokwasser Gate, I was all eyes for Dopsteekhoogte (loosely translated from the apt Afrikaans name as ‘Have-a-drink heights’). In the 1950s a convoy of farmers would stop on the top of hills on their three-day trek to the coast and open their bonnets to let their engines cool. On one of these passes, Frikkie Bester had a narrow escape when the back wheel of his heavily-laden bakkie slid off the road and the vehicle tilted precariously over the edge, anchored by a ‘witgatboom’ (shepherd’s tree). When the vehicle was back on the road and they reached the top of the mountain, they stopped to rest. The golden sun lit up the vista and the relieved Frikkie went to fetch some sweet wine and a glass from his bakkie and passed it around, thanking all his friends for their help. Everyone had a ‘dop’. It became a local tradition after that to stop and have a drink at Dopsteekhoogte.

I braked in a cloud of dust when I nearly missed the words ‘Dop steek’ untidily painted in white on the rock. I turned back to the viewpoint and walked around. Someone had placed an old pair of shoes on the bench and I wondered whose they were as I breathed in the vast landscape. The land now had a wonderful grassy hairdo, an auspicious omen that the long drought had finally broken and the land had been blessed with rain.

Two shepherd trees entwined in a lovers’ embrace with a view of the sweeping landscape caused me to brake in a cloud of dust again. And then it was time to turn to the north to Palmwag Lodge and Camp, my destination for the next few days. I passed through the veterinary gate and turned towards the small oasis surrounded by the magnificent burnished mountains, ending the route along the Skeleton Coast with as much romance as it could muster, a red sun dipping behind the silhouettes of palm trees into the land of basalt like a precious ruby dug out from deep within the earth. I could only raise my glass in awe and give thanks for a fascinating day and adventure of history, sea and land – romancing the Skeleton Coast.

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT