by Manni Goldbeck

While hiking on Brandberg many years ago, I came across the wreckage of a small plane. It fascinated me and got me wondering how it had ended up there . . .

Thanks to the account written by Peter Bridgeford and Tim Botha’s recollections shared with me in February 2021, I learned what had transpired on that windy day of 12 June 1964.

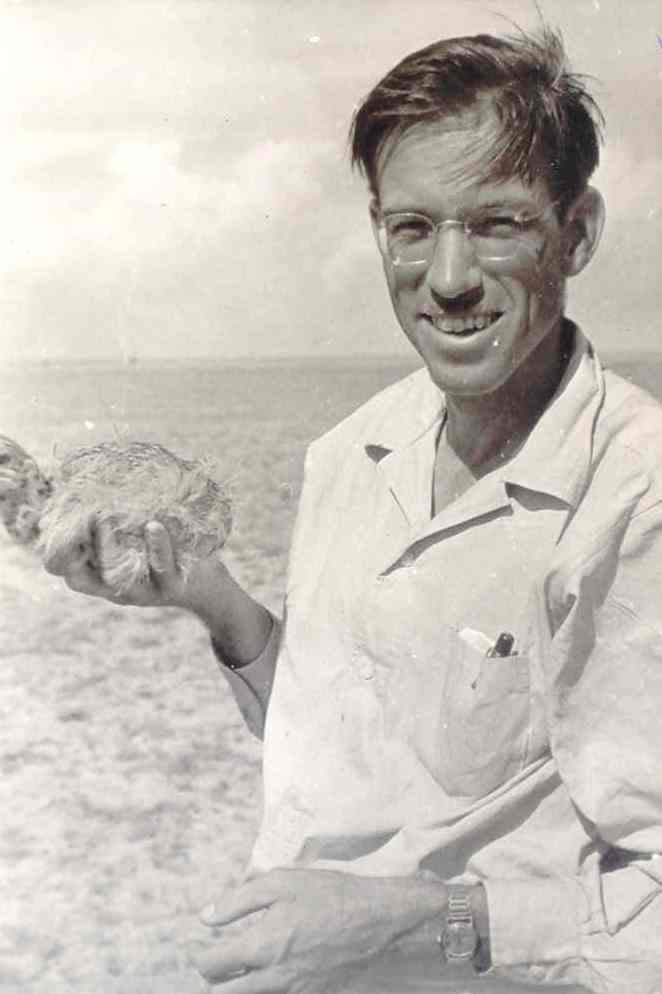

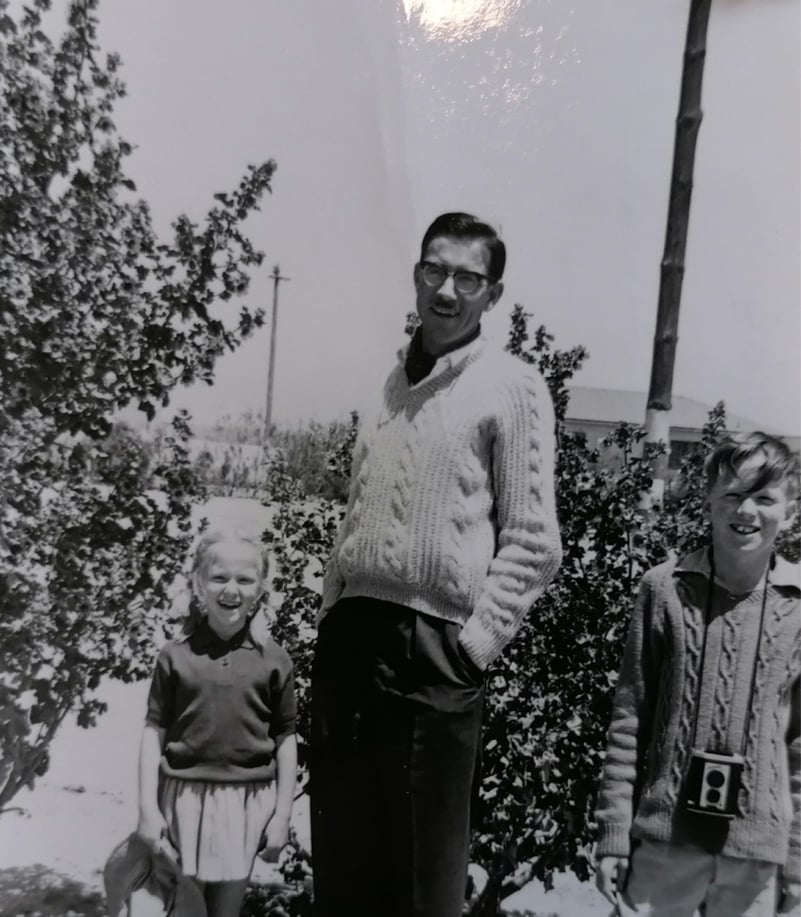

Brandberg, Namibia’s highest mountain, has always attracted hikers and climbers. In the 1950s and 60s, it also attracted Jan Botha, a geologist and manager of the tin mine in the nearby town of Uis. In his spare time, Jan would drive the twenty kilometres to the mountain and explore the surroundings on foot. On one of his hiking trips, he found a wide plateau which he thought would be suitable as an airstrip for his light aircraft, a Piper Cherokee 180.

The plateau was on the south-eastern side of the mountain at an altitude of about 2500 metres above sea level. He and a worker from the mine made many trips to the mountain, hiking the few hours up to the site with a sledgehammer and shovel to remove the rocks and level the ground. When he could land safely on the airstrip, he transported a compactor to the site in the Piper and compacted the soil. He marked the centre of the airstrip with whitewash and erected a windsock. His son, Tim, although a child of twelve at the time, remembers how passionate his father was about the mountain and the construction of the airstrip.

In June 1964, Jan arranged for four hiking friends from Walvis Bay – Lodewyk Platte, Bob Stanley, Fred Fillitz and Franz Mildner – to hike up to the airstrip and meet him there. He would fly in the Piper, carrying enough food, water and equipment for the next few days so that they could hike from there to Königstein peak, the highest point of the mountain, and spend time exploring and enjoying the area.

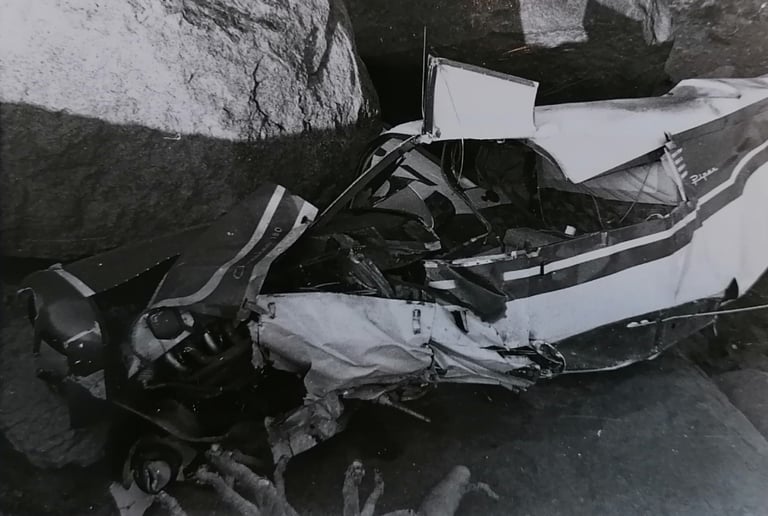

The group arrived at the base of the mountain on Friday 11 June and started climbing early the next morning in a very strong east wind. As they ascended, they heard the sound of the Piper with Jan and Tim on board on their way to the airstrip. The sound of the engine suddenly ceased and in the distance they saw a cloud of dust or smoke rise up into the sky. Shocked, they hurried up the mountain, giving way to a leopard they encountered along the path. When they reached the airstrip there was no sign of the plane. Searching the area, they came across the wrecked aircraft wedged between the rocks, two hundred metres away.

The one wing had been torn off and was partly burnt, the other was jammed under a huge boulder and the cockpit was balanced four metres off the ground. The camping equipment and supplies were scattered on the ground. With hearts racing, the hikers approached the wreckage to find an injured Jan and Tim still strapped to their seats. Tim remembers that fateful day before he lost consciousness. He recalls how the weather conditions weren’t ideal, but because his father didn’t want to disappoint the hikers, he attempted to land the small plane in the gusting wind.

The four hikers forced open the roof of the cockpit and removed Jan and Tim, who looked like they had sustained serious injuries and lost a good deal of blood. Once they had made them as comfortable as they could on the ground, Platte and Stanley set off down the mountain to get help. Night was already approaching and they had to negotiate their way by torchlight.

While the two hikers made their way down, the mine personnel, realising that the plane hadn’t returned to Uis, were searching around the base of the mountain. The hikers signalled to them with their torches and the two groups met at around midnight. By 2am they were at the mine in Uis organising a rescue. Fillitz and Mildner, who remained on the mountain, moved the injured pair away from the wrecked plane in case it toppled over and spent the night in the bitterly cold wind trying to keep them warm.

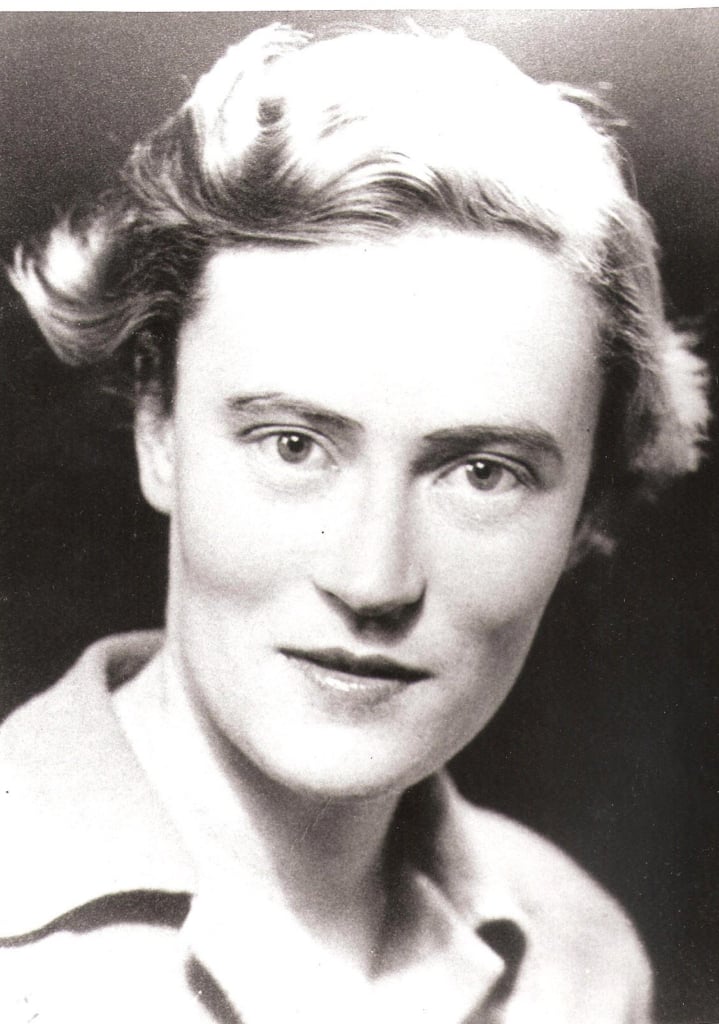

At 8am on the Sunday, veteran WWII pilot, Wolfgang Schenck, arrived in Uis flying a Suidwes Lugdiens (South West Airways) Beaver DHC-2. The strong east wind prevented his first attempt at landing on the Brandberg airstrip. He relayed a message that he would return every two hours to check if the conditions had improved. For the injured on the mountain, it became a race against time, a matter of life or death. Eventually at 11.30, Schenck managed a hair-raising landing on one wheel with the right wing clipping the ground. A shaken Dr Freda de Jager emerged from the plane with him. The two hikers helped to turn the plane around while Dr de Jager examined the injured father and son. Tim was in a more critical condition, so it was decided that he should be flown out first. The Beaver bounced down the airstrip, dropping over the edge of the mountain, and flew Tim to Uis. From there he was transferred to a larger aircraft and flown to the hospital in Windhoek. Schenck then repeated the trip to collect Jan, who was also transferred to Windhoek, and to collect Fillitz and Mildner. Although Jan’s head and feet were injured and Tim had broken his pelvis, in time they recovered to tell the gruelling tale.

Two years later, on 11 June 1966, Wolfgang Schenk returned to the Brandberg airstrip, accompanied by Namibian businessman Willie Celliers and aircraft maintenance engineer Wolfgang Grellmann. Celliers had purchased the wreckage of the Piper from the insurance company to salvage what was left. When they had salvaged the engine, instruments and seats, Schenck gunned it down the bumpy airstrip for the last time and flew out of the valley.

Today, the fuselage and wings of the Piper Cherokee remain on the mountain, making every hiker who comes across them wonder what drama had played out on Namibia’s highest mountain.

(Reference: Adventures on the Brandberg, Peter Bridgeford, Mitteilungen/Newsletter 55: 5-12 (2014))

Watch this space next Friday for the next drama on the Brandberg airstrip . . .

%20(1).png)

.png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT