Linking the Little and Great Karoo is Meiringspoort, a beautiful meandering 16km route through the Swartberg mountains that has 25 drifts where the road crosses the river. Each has its own fascinating story.

The first tale to tell is the one about Petrus Johannes Meiring, a farmer from De Rust who crossed the range in the 1800s, created a bridle path along the Groot Rivier with fellow farmer Gerome Marincowitz and then campaigned for a pass to be built between the towns of Klaarstroom and De Rust.

This dream came to fruition years later, when in August 1854, the two great road engineers, Thomas Bain and his father, Andrew Geddes Bain, set off on horseback to look at the lay of the land. The pass, built by a team of paid labourers over 223 days and costing £5 018, was opened on 3 March 1858. On the grand occasion of its official opening there was a procession of 12 wagons, 50 carts and 300 horsemen. It connected the hinterland to the port at Mossel Bay and enabled Karoo wool to be transported to the harbour. The slower route along the Swartberg Pass was constructed in 1887 after the frequent flooding of Meiringspoort, providing an alternate route.

The first road in Meiringspoort was known as the ‘Boer Road’. It was upgraded several times over the years until it became the well-tarred road through the sandstone mountains that we enjoy today.

One of the most popular spots along the route is a waterfall that plummets into a rock pool below. The steps and footpath leading to the waterfall were hewn into the rock when the Prince of Wales visited in 1925. People believed the pool at the bottom of the waterfall to be bottomless, but a team of divers proved this to be a myth when they ascertained that it was 9 metres deep. It is said to be the home of a fresh-water mermaid. Some think that she was washed out by floods or was caught in a fisherman’s net.

The old toll house and gate, no longer in existence, at the southern entrance to Meiringspoort, was operated by a Mr Rankin, who was also a dentist and herbalist, someone who would have been in demand if you had need of either.

Afrikaans writer, CJ Langenhoven, described the winding road with these words: ‘In every drift there is a bend and around every bend there is a drift.’ He spent time relaxing near the rocks at ‘Herrieklip’, where he chiselled the name of his imaginary elephant friend from his books into the rock in 1929. The drift is also known as ‘Nagasdrif’ after the chief of a San group that lived in the mountains.

Some other colourful names include ‘Nooiensboomdrif’ (Maiden’s Tree Drift), so named after two large Kiepersol trees or cabbage trees (‘nooiensbome’) that once grew on opposite sides of the road and had interlinking branches.

‘Skelmkloofdrif’ (Scoundrel Drift) has a well-hidden ravine on the eastern side that was said to have housed some scoundrels who stole Petrus Meiring’s sheep. His wagoner’s boots were washed away at ‘Steweldrif’ (Boot Drift).

‘Uitspandrif’ (Outspan Drift) had an area that was large enough for a wagoner to outspan his team of oxen, while ‘Wadrif’ (Wagon Drift) was the point where several wagons were washed away.

An otherworldly ball of fire was supposedly seen at ‘Spookdrif’ (Ghost Drift), giving this drift its name.

Travellers entering the poort from the northern side were able to wash off the Karoo dust in the deep pools of ‘Wasgatdrif’.

‘Witperdeddrif’ (White Horse Drift), also called ‘Rabbi se Drif’, is where a Rabbi was washed downriver with his cart and horses. Other accounts mention that the name refers to two white horses that drowned there in the 1915 flood.

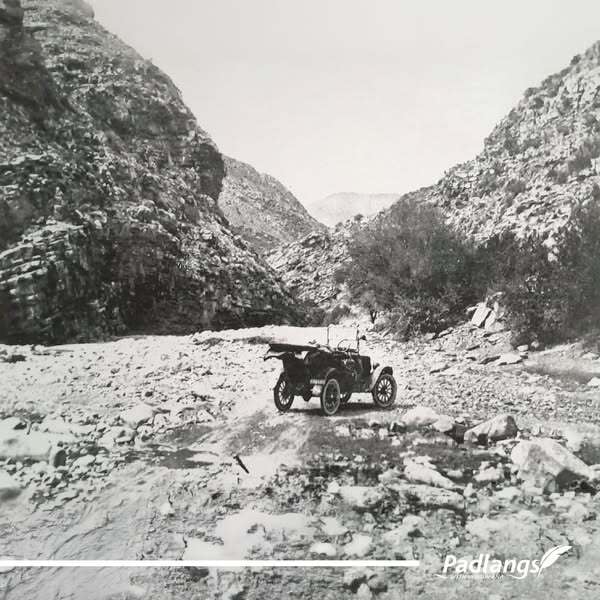

Helena Marincowitz collected some of the local Meiringspoort stories. In the story ‘The minister and his Ford’, Annette Cloete from Oudtshoorn remembers how her father, Rev JA Retief, would drive with the family from De Rust to Klaarstroom in his Model-T Ford to work on the church he was building there. They travelled on the Friday, he worked on the Saturday and on the Sunday he conducted a service under a tree before driving back to De Rust. Annette recalls how at the first drift water would splash up and the engine would stall, and how her father would remove his frock coat, socks and shoes, roll up his trousers, push the Ford through the drift and then dry the damp components with his handkerchief before they got underway again.

Another story describes how people were marooned in the poort when the river came down in flood. A retired farmer, Pieter Burger helped many of these travellers. In the flood of 1946, motorists were stuck in the poort for three days. In the 1968 flood Burger rescued three German visitors with a child when their Kombi was washed away at ‘Aalwyndrif ‘(Aloe Drift). One of the men climbed a tree with the child, while someone else swam to fetch help, climbing out of the river at Spookdrif.

‘Double Drift’, where the Groot Rivier snakes sharply between the rocky walls was feared and children would keep their eyes tightly shut until they were safely through. The wagon would still be in the first drift while the oxen were already in the second. This is also the site where a couple drowned, and the remains of their horse and buggy were found. They had attended Nagmaal in De Rust and had travelled on the Sabbath to return home to their children, who were ill with measles, in Klaarstroom.

On a more positive note, Meiringspoort was a gathering place at New Year in the 1930s when people from the surrounding farming communities would come for a two-day celebration. They brought their guitars and accordions, danced the ‘tiekiedraai’ and dipped in the pools. The ‘ooms’ would challenge each other at target practice while the ‘tannies’ unpacked their crates of delicious homecooked food. It was always over far too soon and everyone would have to leave the spectacular setting of the poort to return home.

(References: Meiringspoort Drifts - Oudtshoorn Info; Meiringspoort - Wikipedia; Information boards, Meiringspoort; Prince Albert Local Stories, Helena Marincowitz, Fransie Pienaar Museum, 2000)

%20(1).png)

.png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT