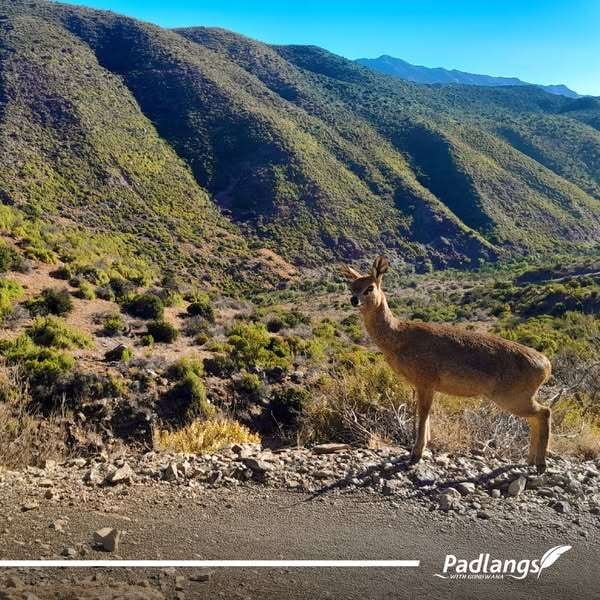

The winding gravel road down into Gamkaskloof began sedately for the first 30km, lulling us into an easy travelling reverie before shocking us into action for the last ten, with a rocky switchback track (barely wide enough for a single vehicle) that needed all our concentration. It wasn’t only the road that got our attention as it zigzagged its way down through the Swartberg mountains. We were awestruck by the spectacular scenery around us, a world of exquisite beauty, giving us the impression that we were entering a magical kingdom of old. A family of klipspringers stopped statue still and gawked us, and as we bumped over the last rocks to level ground at the bottom with a sigh of relief, kudu watched us with large, curious eyes and ears alert before turning tail and disappearing into the trees. What we had already realised from way above was that Gamkaskloof is far from being a hell, but is rather a lush, fertile heaven blessed with underground water.

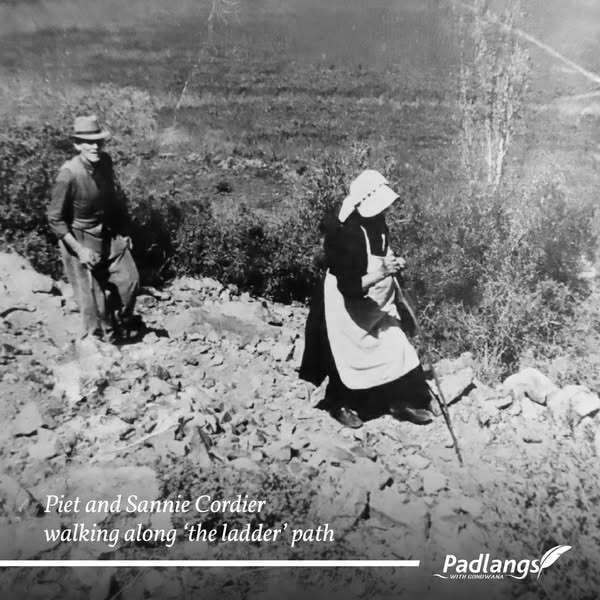

Where did it get it notorious name ‘Die Hel’ from then? Well, back in the late 1700s when the first farmers made their home here, it took considerable effort (more than the 2 to 3 hour drive down the pass today) to get in and out. The route on foot with donkeys carrying packs was via the rocky riverbed and on footpaths through the mountains, the best-known one being to Calitzdorp via a steep incline dubbed ‘the ladder’ for obvious reasons. The hard life and difficult access routes were, we presume, a bit of hell.

Besides being held gently in the arms of the generous mountains, creating a secret hideaway, the area has a fascinating history. Marinette Joubert from Fonteinplaas sat down with us in ‘Ouma Sannie se winkel’, filled to the brim with a mouthwatering selection of jams and preserves made lovingly from farm produce, and told us the tale. The family’s small Yorkshire Terrier was curled up on a chair and the sunny day beckoned outside with all the gusto it could, as befits a day in the Klein Karoo.

This little pocket of the Western Cape had in early times seen many Khoisan travellers, who slept under the overhangs and painted their life in sienna shades on rock walls. Other travellers passed by in later years, following the Gamka River, which provided a ‘poort’ or gateway into the valley. It was only in 1767 that nomad farmer Pietrus Swanepoel entered the valley, saw the many springs and fertile soil and decided to stay put.

As Marinette began to tell the story, the rest of the world disappeared and we journeyed in our imaginations with her back in time. “Hendrik Mostert, my mom-in-law’s great grandfather, bought this farm in 1841,” she told us. “By then he was the third owner of the farm Fonteinplaas.” Twenty-six families lived in the valley that was divided into three sections: Boplaas, Middelplaas and Ouplaas. Their surnames were mostly Cordier, Mostert, Marais and Swanepoel. The families were subsistence farmers and lived an isolated life away from the rest of the world.

She added an interesting snippet of information that during the Anglo-Boer War, Boer commando Deneys Reitz stayed with the Cordier family, on her mom-in-law’s mother’s side. Grandmother Cordier gave him food and clothing, and when he left, he presented her with a silver snuffbox as a gift to thank her for her kindness.

In 1926 a primary school was built in Middelplaas, which ran until 1980 when it closed because of a lack of pupils. “During this time, they had about thirty teachers,” Marinette informed us. “They didn’t stay long.” Only one teacher brought his family with him and stayed for eleven years. His eldest daughter returned years later and left a small bag with five stones (representing her family) with the Jouberts, asking them to keep it safe in the valley and leaving with the words: “They were good memories; I’m leaving my heart here.”

It was only in 1962 that the snaking road down to Gamkaskloof was built, as it had been decided to build the Gamkaspoort Dam, which would block the residents access to the village via the poort on its north-western side. Koos van Zyl was the operation manager who built the pass with eight workers and only one piece of machinery, occasionally enlisting a professional for the dynamiting of the difficult sections. It took them two years of sweat and toil.

The first car, however, had already entered the village through the riverbed in October 1958, as an adventurous expedition over the river rocks. When Tulbagh’s Ben van Zyl and friend Isak Burger visited Die Hel and arrived at Oom Snyman’s cottage, he told them that there was nothing mechanical in the valley. They decided to buy an old car and return with it, to be the first to bring a vehicle into the kloof. This they accomplished with the help of four donkeys that pulled the Morris Eight over the rocks and through the sand. It took them about thirteen hours, from morning to night, to traverse a stretch of thirteen kilometres. Oom Snyman had been a truck driver in the Boer War and knew the mechanical side of cars. The friends stayed with him for a night or two, left the car with him and walked out.

When the Gamkaskloof children were of high school age, they left to attend boarding school in the nearby towns of Calitzdorp, Laingsburg, Oudtshoorn and Prince Albert. Marinette’s mother-in-law, Annetjie Joubert (née Mostert) went to boarding school in Calitzdorp, walking the 9km through the riverbed to Matjiesvlei where her uncle farmed. He gave her a lift the rest of the way in his vehicle. Life changed in the village when the older children left and few wanted to return to a farming life. When the school closed in the early 1980s, many of the families with children left and moved out of the valley. They began to sell their properties. Most were sold to Cape Nature.

The Mosterts also decided to put their property on the market, but Annetjie and her husband Bennie Joubert decided that they wanted to keep it in the family and bought it from her parents. They lived in Robertson at the time and it would only be 28 years later, in 1998, that that they would return with their son, Pieter, start renovating Oupa Piet’s cottage and rent out great-grandfather Mostert’s house to visitors. The fruit trees were still there, but with the challenges of baboons, kudus and birds nibbling their produce and the distance to the towns to sell fresh produce, they decided to start a campsite.

Pieter Joubert met Marinette in Prince Albert where she grew up and she moved with him to his family farm at Fonteinplaas when she was 21. They ran the campsite with mother-in-law Annetjie, homeschooling their children Mia and Beon. Over the years they renovated some of the original farmhouses and buildings, which they now offer as accommodation, and also built an attractive safari bush camp. Marinette runs the rustic restaurant, offering a new menu every day, depending on what’s in stock, and providing delicious salads, breads and traditional boerekos suppers for guests on request. While she has her hands busy, Pieter, who has delved extensively into the history of Die Hel and compiled a book, offers historical tours with a witblitz tasting and a picnic at the river; and Mia and Beon offer a nighttime scorpion tour, using their knowledge of thick-tailed scorpions and their deep love and respect for the natural world garnered from their parents to entertain guests and generate some pocket money.

Before we stocked up with jars of preserves, enjoyed lunch in the garden and went to look for the old school and houses, we paged through the albums with their collection of black-and-white photos of Gamkaskloof, and Marinette pointed out family members and the people who had lived there and made Die Hel their home. The farms are all long gone now, except for Fonteinplaas and Boplaas, ten kilometres away, and the Cape Nature office has closed its doors for the time being. All that’s left are the delights of the guestfarms, quaint renovated houses, ruins, a rich history and the beauty of the valley.

Entertained and enlightened, we said our goodbyes to the friendly family, explored the area and then braced ourselves for the steep route out.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT