Ruins of century-old lime kilns, once essential for construction, lie hidden in the Namibian countryside. I went searching . . .

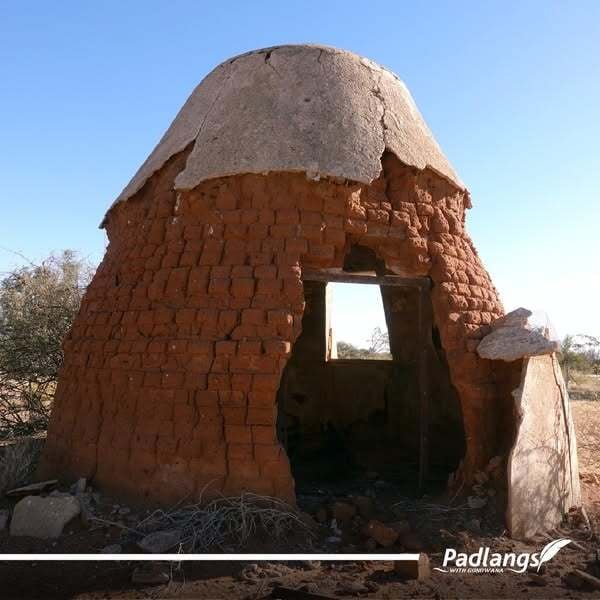

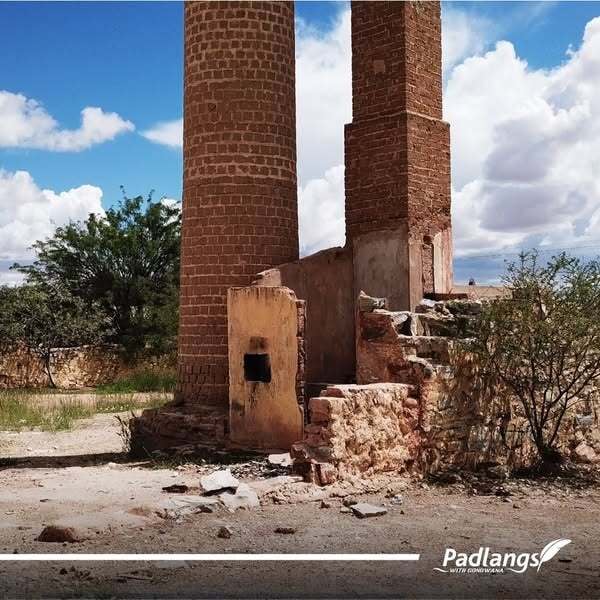

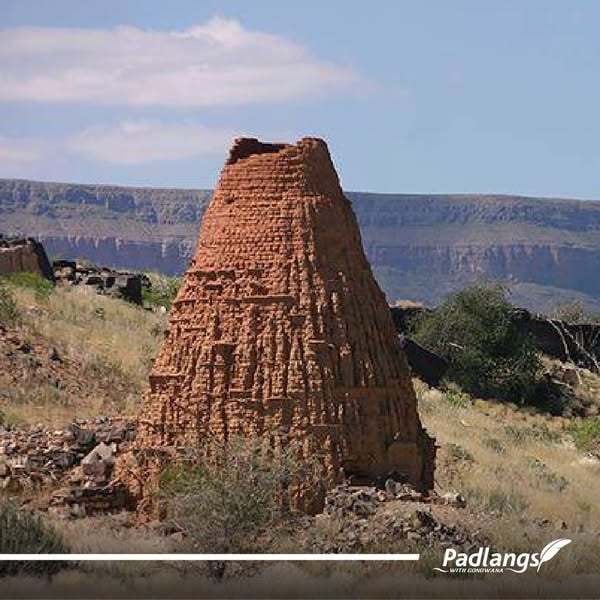

I found them, one by one, in different areas of the country standing like proud old monuments, testifying to a time when life ticked at a slower pace. It wasn’t easy. They were deeply hidden on private farms, near railway lines and along gravel tracks that led over rock and riverbeds into overgrown thorny bush that scratched my skin and ripped my clothes. But, it was worth it. The conical clay-brick or stone chimneys - kilns or ovens - used to produce quicklime for mortar, are prized relics of the past, housing memories and holding rich stories of both hardship and hope.

Traditionally in Africa, houses were built with whatever natural material was available in the area: mud, dung, sticks, rock, reeds and clay or even grass mats like the Nama’s original ‘matjieshuise’ that could be dismantled and rolled up when they moved on in search of better pasture. When Europeans came into the country, they built their early houses called ‘hartebeeshuise’ from a combination of natural material, often with a grass roof. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, they brought with them the knowledge of using lime to construct more permanent homes. The lime kilns changed the lifestyle as it was known until then as people began to build European-style houses.

Namibia was an ideal environment for this modern building method with its vast landscapes where carbonate rock (limestone, ‘kalk’/chalk) is commonly found. Many place names attest to this fact - like Kalkfontein, Kalkfeld and Kalkrand. The early Europeans put that knowledge into practice. In the days before cement was easily available and affordable, many a farmer built a lime kiln on his farm, often next to a riverbed, for the construction of the family home or to sell commercially to other farmers or in the towns as the demand grew. Commercial lime kilns were usually built near lime deposits and railway tracks, to allow for easy transportation.

It was a laborious, back-breaking and time-consuming process that involved breaking limestone rock into manageable pieces and conveying it in ox-wagons to the lime kiln, as well as collecting a large supply of wood from the river beds. The wood and stones were then packed in alternate layers, a procedure that alone could take at least a day or more. The work didn’t end there, and a fire had to be lit, heating the rock to temperatures above 825°C to produce burnt lime or quicklime – Calcium Oxide (CaO), which fell to the bottom, where it could be raked away with a shovel when cool. This handy substance was used for building, to be mixed with water to form slaked lime for use in mortar and plaster or to whitewash walls.

After Gondwana published the initial article about lime kilns in the newspaper, people contacted me to let me know where others could be found and I gradually followed the leads and went chimney-hunting. It took almost twenty years of research to find all the kilns. I travelled along rural roads, contacted farmers to request permission to enter their property or to ask them if they knew the whereabouts of a possible kiln or ‘Kalköfen’, as it’s known in German. The search took me into people’s houses where over coffee or cold juice, depending on the season, they related stories from their childhood. It even took me to a retirement village where I managed to speak to a man who had built his very own lime kiln.

It’s not often these days that you have a chance to talk to someone who built a lime kiln, but about fifteen years ago I had the good fortune to meet with Wim Botha in Otjiwarongo. His family had travelled to South West Africa after WWI when Wim was just a boy. Wim’s father hired an entire train to transport his animals and the family from the Free State in South Africa to Kalkfeld. When Wim and his brother reached a certain age, he gave them the farm Geduld (Patience) and 300 sheep to earn a livelihood. Initially the farming went well, but eventually over the years and after a series of droughts the grazing diminished and it was difficult for them to make a living. Wim came up with the idea to build a lime kiln and to sell lime for additional income. He ordered special Chamotte clay bricks from South Africa to construct the kiln and bought an old truck to transport lime to Outjo and the surrounding farms. The labour-intensive work involved a continuous process of collecting rock (sometimes dynamite was first needed to loosen the rock), conveying the chunks in baskets to the kiln and gathering vast amounts of wood to build up the fire and sustain the intense heat required to produce the quicklime. Game also had to be hunted for the pot to feed the workers.

Times changed after WWII with the development of large cement factories in South Africa and with the ease and convenience of railway transportation. Eventually, Wim’s commercial lime business, like many of the other small lime industries in the country, closed down. He bought a farm further east and the family moved on.

Today, only about twenty lime kilns remain dotted around the country, most hidden on farmland. Some, however, can easily be viewed, like the one along the roadside at Holoog in the Gondwana Canyon Park and the kiln at Alte Kalköfen Lodge, off the B4 to Lüderitz.

It’s a strange feeling to walk around the old lime kilns. Some have crumbled, some are overgrown with vegetation and some are inhabited by bees, bats and snakes. If you give free reign to your imagination, however, you can take a step back in time to smell the dust and the fire, and to sense the bustle that surrounded them a hundred years ago: people shouting instructions, women delivering basketfuls of rock and men adding chunks of lime to the top of the kiln, chopping wood and raking up the burnt lime, as the hungry fire roared inside.

And then, the moment ends and you are left standing alone in the landscape a century later next to the robust old chimney - in silence - with history hovering close by.

You pause for a few moments, as the commotion in your head stills, and then nature intrudes once more. Birds sing and insects buzz, and you continue with your day, paying tribute to the workers and the lime kilns of long ago, icons of hard work and industry.

(Watch this space next Wednesday for an intriguing biography of a lime kiln)

%20(1).png)

.png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT