Set in southern Namibia, Great Namaqualand, ‘Bittersweet Karas Home’ is the story of three families, the Hills, Walsers & Hartungs, whose lives merge and intertwine in a semi-arid land that presents both hardship and blessings. Over the next few months, we would like to share this bittersweet saga with you from the (as yet) unpublished book.

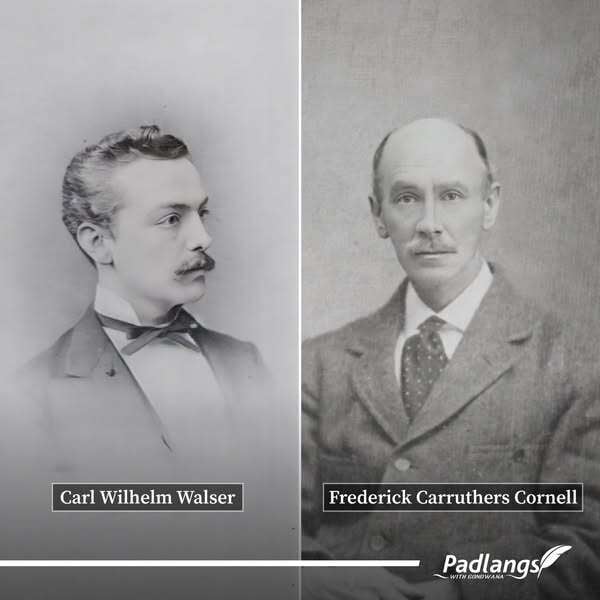

Second and third generation Walsers

During the lull in the South West Africa Campaign in 1914, Charles Adrian Walser married Sarah Elizabeth Fincham in Groot Chwaing near Vryburg. A son, Roydon, was born to the newly-weds in 1915. They moved to South West Africa in 1917 where their daughter Phyllis Natalie Atholl was born in 1919.

Sarah’s parents were Arthur William Fincham and Elizabeth van der Linde. The Finchams were the descendants of brothers who came to South Africa from England in 1829 and settled near Kimberley and in the Eastern Cape. The Finchams were a family of good standing in the Vryburg and Kimberley world. Sarah’s father was mayor of Vryburg and marrying Charles Adrian, a struggling Kalahari farmer, was marrying below her social rank.

Roydon and Phyllis were a source of joy for the family and for a time it seemed as if the happy Ukamas days would return. The Walsers did not benefit from the change of government. They would receive remuneration only for those war damages that could be traced to the Union Forces and even that required a struggle with bureaucracy. The general state of post-war impoverishment affected the Walsers, like everybody else.

Almost all South West African citizens had been displaced from the south to the north, from the country to towns and cities, and returned to land that had suffered during their absence. Workers were scarce due to war casualties and also due to the fact that former labourers now engaged in subsistence farming on reserves. Germans had been reduced to half of their pre-war number after repatriations and had lost access to metropolitan financial sources. To make matters worse, drought struck and lasted from 1919 to 1922. Farmers trekked in search of grazing and water and saw their herds dwindle. Locusts from the Kalahari arrived with the welcome rain, devouring the freshly sprouted grass and grain.

Diamond ambitions

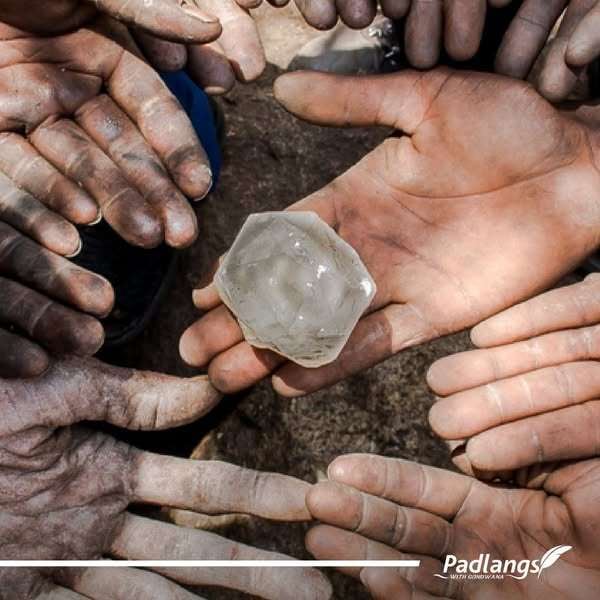

Carl Wilhelm Walser looked east for life-sustaining rain clouds. In the same direction lay Kimberley’s Great Hole or Groot Gat, which he had seen on earlier business trips. In his mind’s eye he could see the jaws of the open-cast mining hole that spewed black dust over the workers and the web of steel-wire ropes carrying buckets filled with blue ground or kimberlite. He shared the southern African dream of finding precious stones.

After the 1867 diamond discoveries, prospectors from Australia, America and Europe flocked to the diggings and pushed aside the Griquas, Kora and Batswana who had initially joined in the rush. Khoi and Africa’s Bantu from as far afield as Natal, Hereroland and Rwanda arrived at the hole as workers. The neighbouring Batswana, Kora and Basters supplied the growing number of people with grain, cattle, game and firewood. International businessmen and bankers followed and would eventually take control.

The Tlhaping and Rolong Batswana and the Kora fought over access to the firewood and food trade and hired Boer and British mercenaries – among them the legendary Scotty Smith. These freebooters wanted to be paid in land and established the short-lived Boer republics, Goshen and Stellaland, on whose territories the Walsers would find their future home. When the days of the open-cast Great Hole came to an end and pits had to be sunk, Cecil Rhodes had bought up most claims with the help of London-based banker, Nathan Mayer Rothschild.

In 1886, when the discovery of the Witwatersrand Main Reef added the Witwatersrand Gold Rush to the diamond frenzy, Cecil Rhodes also managed to seize control. Kimberley and Johannesburg became centres of a mineral-industrial revolution as well as vortexes that dragged southern Africa into the industrial world and transformed and often obliterated former lifestyles.

In 1898, Carl Wilhelm was one of the founders of the shareholding company Deutsches Minen Syndikat (German Mine Syndicate) with other farmers like the Hills, Duncans, Hartungs and prominent businessmen, Seidel, Mühle and Angelbeck. They bought the farm Mukorob from the Berseba Captain and his council and installed Mr Routh as farm and project manager. The map of the Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon from 1920 registers Mukorob as ‘blue ground’ but this was soon found to be barren kimberlite without any hoped-for diamonds.

In 1908, Kimberley-trained railway worker, Zacharias Lewala, found an alluvial diamond, which he handed to his supervisor, August Stauch, who had its diamond status confirmed. A diamond rush to the desert near Lüderitzbucht ensued. Seven million carats were mined until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Private fortunes were made but not by the Walsers who had already fled to Kinderdam. They had also missed lucrative business opportunities. Ex-partner, Hugo Friedmann, provided the German army with whatever horses, saddles, ammunition and food it required from the Cape during the 1903-1908 war. There were extortionate prices to be had and he saw huge amounts of money pass through his hands. He squandered much of his windfall profit on a lavish lifestyle in Cape Town’s Mount Nelson Hotel and had to start again from scratch when the war profiteering had come to an end.

Carl Wilhelm’s friendship with charismatic and passionate prospector, Frederick Carruthers Cornell, appeared promising. Cornell prospected all over southern Africa from 1901 to 1920 without any major success. Carl Wilhelm, however, believed in his abilities, financing at least one of his expeditions and hoped to benefit from Cornell’s future success. In 1921, while Cornell was in London finding a backer for further exploration of the lower reaches of the Orange River (and it was widely believed that he knew exactly where to find that mineral wealth), he was thrown out of the sidecar of a motorcycle in the city centre. His skull was fractured and he died two days later. He had survived many life-threatening African adventures, including a fall from a horse on the farm Arris when his foot lodged in the stirrup and his body was dragged across boulders. Now civilised London ended his life. Carl Wilhelm’s investment in Cornell’s prospecting genius vanished for good.

While the Hill, Walser and Hartung families failed in their quest for mineral riches and German businessmen prospered from diamonds in the years between 1908 and 1915, a process had been put into motion that would lead to a diamond monopoly in southern Africa. Ernst Oppenheimer (1880-1957) left his native Friedberg in Hesse-Nassau to become, at the age of sixteen, a junior clerk of the London diamond brokers, Dunkelsbühlers & Co. In 1902, he worked as their representative in Kimberley. In 1917, with the backing of the London-oriented US financier, John Pierpoint Morgan, he formed the Anglo American Corporation of South Africa. Two years later he expanded to diamond mining on South West African soil and formed the Consolidated Diamond Mines of South West Africa. This corporation was so successful that it enabled him to gain control of the De Beers Consolidated Mines, which Cecil Rhodes had founded, and in 1930 Oppenheimer established The Diamond Corporation. From this position, Oppenheimer strengthened the diamond marketing monopoly initiated by Rhodes and was able to prevent price losses caused by a worldwide oversupply of diamonds.

By 1929, most of the shareholders of the Deutsche Minen Syndikat had died or left the country, Mukorob was discovered to be barren and a global Depression was unfolding. Carl Wilhelm Walser dissolved the company and buried his diamond hopes. The Walsers did, however, roam up and down the Bak River near Ukamas collecting semi-precious stones like tourmaline and rose quartz, enjoying the hobby and the riches the earth proffered.

The next two Walser generations, son Charles Adrian and grandson Roydon, engaged in another diamond quest. They had an old prospector’s diary that referred to a crater in the mountains surrounding the Orange River where there was supposedly an abundance of diamonds. Although they followed the diary’s instructions to the letter, clambered up and down mountain sequences and through gorges carved by the Orange River on its steady flow to the ocean, they failed to find anything of real value.

Precious minerals fire up human ambitions. A few individuals struck it rich. Hundreds of thousands found menial employment in mines or supply systems. Competition between nations escalated to war-like proportions. In the end, the winners were often money-jugglers in giant global corporations. The Hills, Walsers and Hartungs fell under the spell of diamonds, lived through the shocks and aftershocks of gold and diamond frenzies and trekked through a world utterly transformed by the diamond, gold and copper economy. They remained outsiders in a game played by others.

(Join us every Sunday to take a step back in time and follow the interesting, sometimes sweet, sometimes heart-wrenching tale.)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT