Stories of trade, farming and home life in Great Namaqualand

Set in southern Namibia, Great Namaqualand, ‘Bittersweet Karas Home’ is the story of three families, the Hills, Walsers & Hartungs, whose lives merge and intertwine in a semi-arid land that presents both hardship and blessings. Over the next few months, we would like to share this bittersweet saga with you from the (as yet) unpublished book.

Finding one’s place (‘Ti oms') – an Introduction (cont . . .)

The men of these families began life on European soil. In southern Africa, they did not leave their new horizons unchanged, but built windmills, dam walls and dreams. Colonial rule imposed from 1884 brought guns, paper decrees and regulations, often making life intolerable for the indigenous people and for the settlers who had arrived before there were colonies and who had developed their own way of merging horizons.

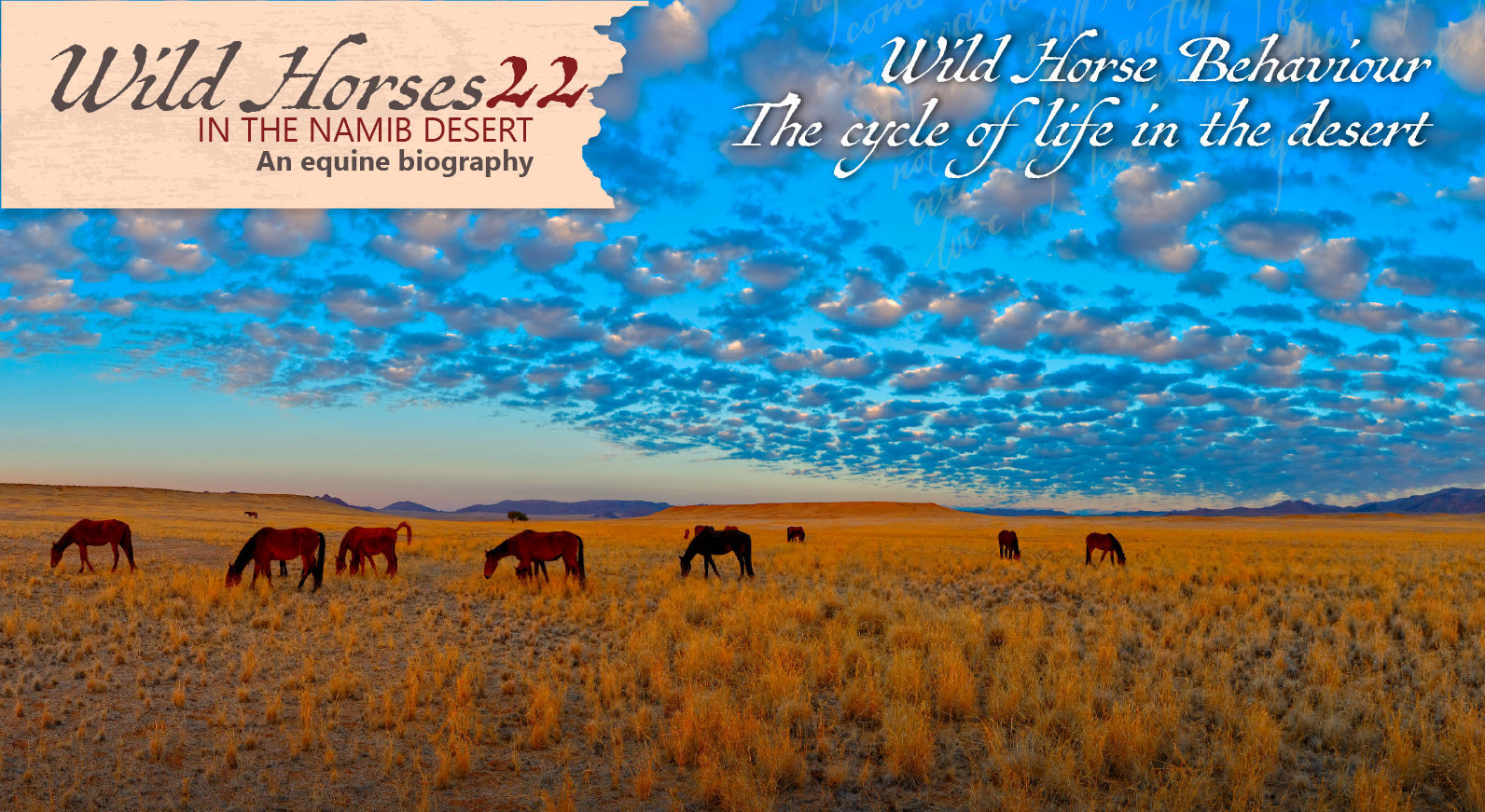

Karas seems to be an unlikely choice for any home. Rain, water and grass are scarce with fewer than 200 millimetres of average annual rainfall; the climate - scorching hot summer days and chillingly cold winter nights - can be hostile. Water evaporation and water deficit rates show that the Great Karas Mountain region is more severely affected than most other Namibian regions. Predatory and venomous animals have to be reckoned with. The Bittersweet Karas heroes and heroines discovered that Karas life can be oppressive.

The concept of ‘home’ can be a house, a stretch of land, the possession of title deeds, a region or a social network, but in an arid world its centre is always a water source: a well, trough or dam. It is handed down from generation to generation, praised in songs and remembered in tales.

Being human means that we need a home, a circumscribed, friendly man-made environment, a place to love and be loved. It is based on patterns of human togetherness and always has to stay ahead of decay and degradation. Journeys allow us to bring back souvenirs and ornaments for the home and ideas of how to improve and reinvent it. Home is about family, but can include clan, community, nation and humankind; concentrically linked communities of increasing complexity.

Different generations experience home differently. Home routines may confine and bore adolescents who may run away with the confidence that they will find and build better homes elsewhere. They may be driven by an inexplicable travel drive. The Boers (Afrikaans-speaking farmers) refer to it as ‘trekgees’ and practised it extensively, and the Germans talk of ‘Wanderlust’ or ‘Fernweh’, a powerful yearning for faraway places that can make you as sick as homesickness. Some even dream of finding a home in homelessness.

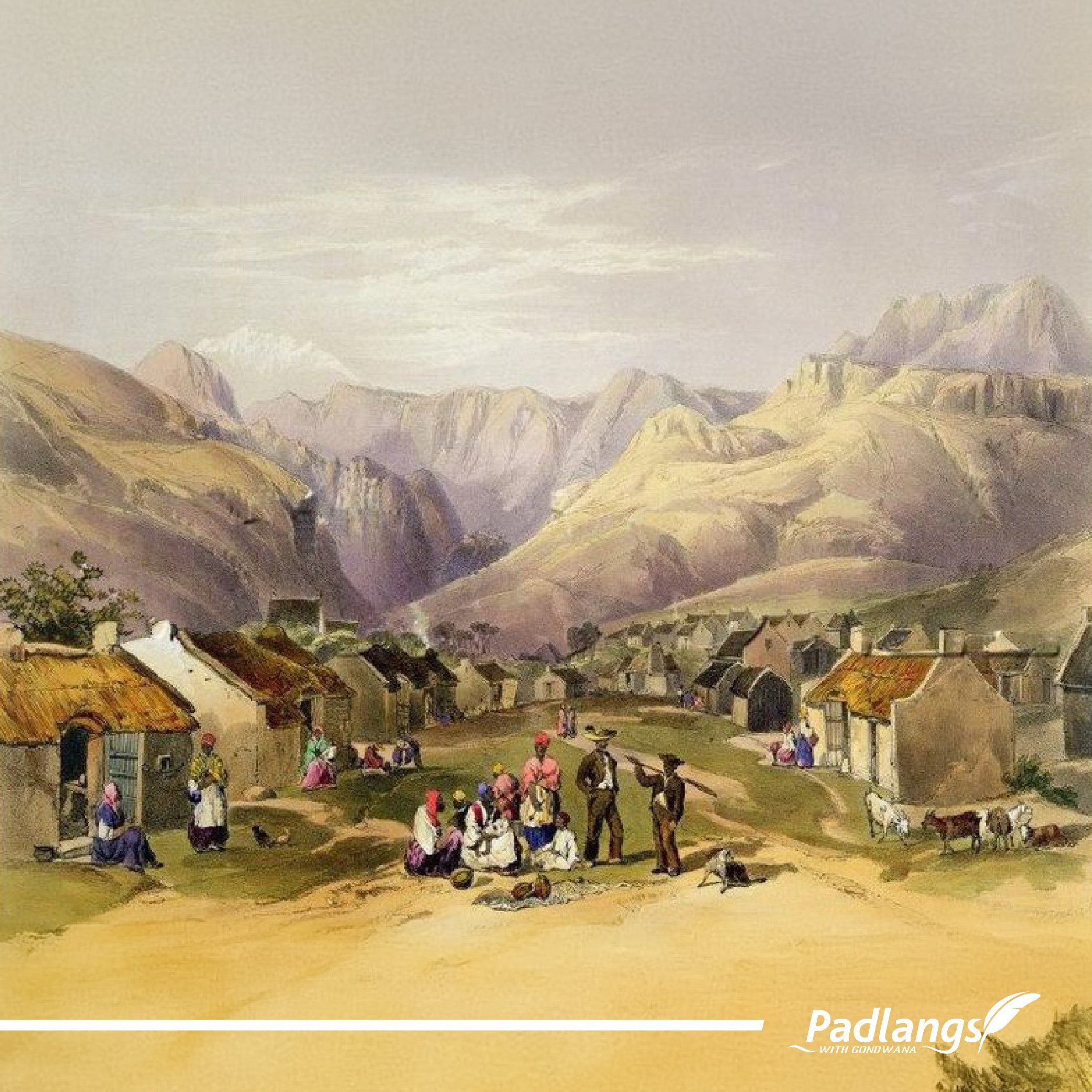

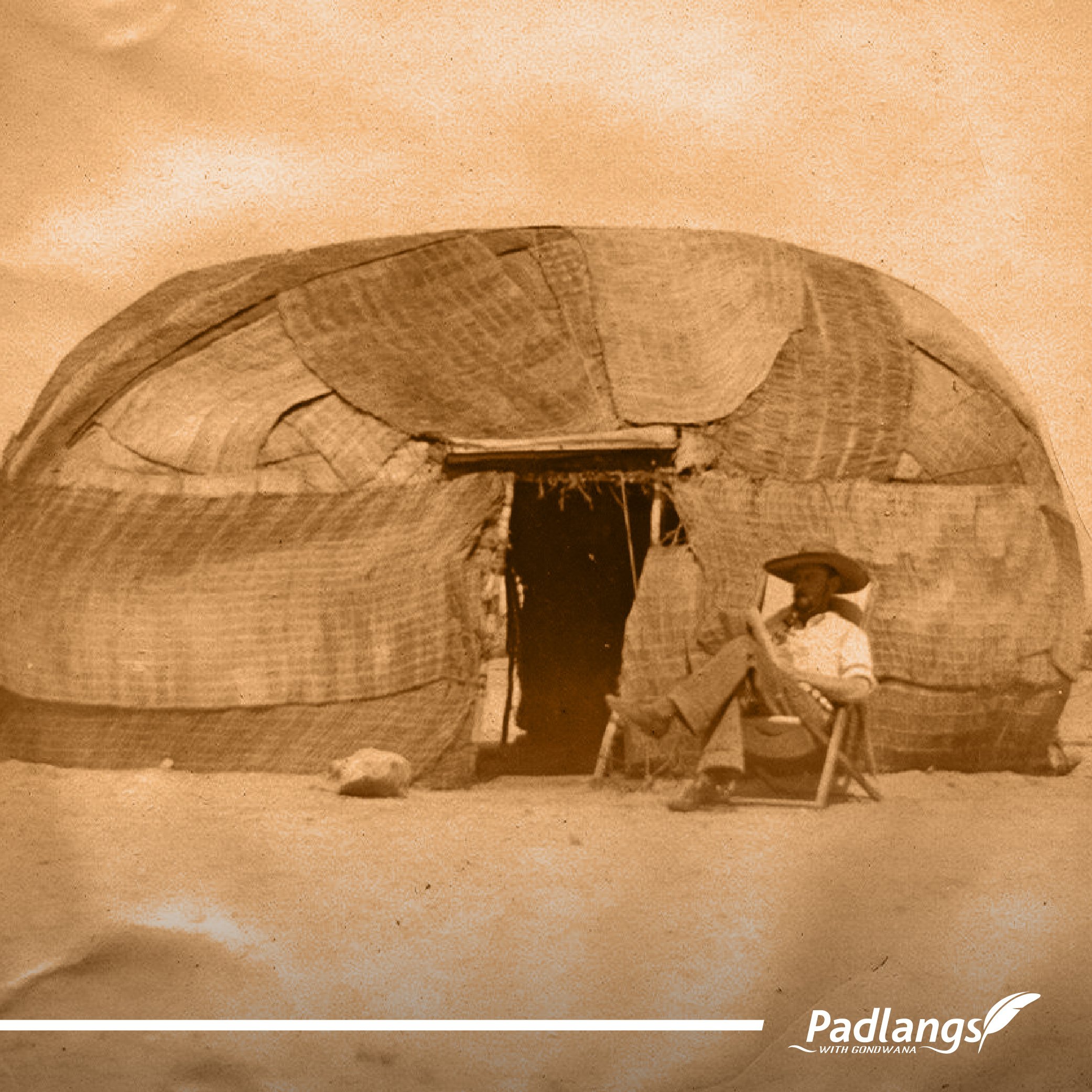

Traditionally, southern Africans were nomadic and semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers and pastoralists with cattle, sheep and goats. That, however, does not mean that they were homeless. Most nomads shuttle between summer and winter homes, bordering pastures of sweet or sour grasses that are palatable for livestock in alternating seasons. Their homes were often transportable; cultural patterns and social structures were incorporated into this way of life.

Even San hunter-gatherers had a clear idea of home and preserved detailed maps of it in their memories. The Khoi or Nama people of Great Namaqualand, north of the Orange River, were well-acquainted with the drought and heat that could settle on the earth and they knew the land intimately, as did the Hills, Walsers and Hartungs. They looked wistfully at the high Bushman grass when it was green and blowing in the breeze, recognising its fleeting display of abundance. They depended on milk (soured in a calabash) and meat from their flocks and herds, but looked to the veld for its seasonal gifts. Honey, roots, wild game, grain collected by ants and the rich contents of ostrich eggs supplemented their diet. Every meal was to be shared amongst the group, with everyone benefitting in times of plenty, but the children also knew from early on to suck the gum from thorn trees when their stomachs rumbled and the earth was dry.

African homes also have a spiritual dimension and include the living as well as the dead. Even people without a belief in the ancestor afterlife may perceive their family home as the amalgamation of the dreams, insights, suffering and joy of past, present and future family members.

Stories move forwards and backwards between harmony and imbalance. Migrants like the Hills, Walsers and Hartungs moved from birth homes to foreign countries where they built new homes. Migrants are pushed from their place of origin or abandon it, but always retain the hope for new homes and better lives elsewhere.

From the early nineteenth century, southern Africa saw an explosive chain reaction of migrations, linked to and often triggered by a global migration surge emanating from a rapidly populating Europe. The human biographies that unfolded were about pursuing dreams while learning to coexist with those who were there before them. ‘They’ and ‘we’ interacted in different ways and strangers became friends or foes depending on the form of interaction.

Migrants can exchange skills and goods that increase and diversify life and production, establishing a mutually beneficial system. This is what the Bondelswarts apparently hoped for when they sold land to settlers like the Hills and Walsers.

Missionaries played a role in the Hill, Walser and Hartung families as ancestors and as mentors. Many of them were trained artisans. They sometimes succeeded in creating model communities like Genadendal, Khubus and Wuppertal, which would feed and further advance their inhabitants, and later on shelter them against some of Apartheid’s hardships. They also had to learn how to cope with environmental degradation that was inadvertently brought about by higher densities of people and livestock.

Building bridges, however, between ‘us’ and ‘them’ was not what colonialism was about. It established domination. The San, the original people of southern Africa, had been pushed into mountains and deserts and their numbers had dwindled. As nomads they were assumed to have no attachment to land.

The colonial administrators benefited more from the escalation than from the resolution of conflict. Indigenous people who had been pushed towards revolt and had been defeated could easily be stripped of land and livestock.

Colonialism, in whatever form, turned the newcomer-indigenous people, the ‘us-them’ relationship on its head and the ‘Scramble for Africa’ gave everything an additional twist. The name ‘German South West Africa’ was an open-ended invitation for Germans to settle and other Europeans depended on their good will for the right to reside in the country, while locals could only aspire to second-class citizenship. Indigenous self-government was rejected, indigenous land was declared Crown land and home rights were restricted to ‘reservation homelands’.

After the South African victory over the Germans in 1915 and the Treaty of Versailles, the land became, in essence, (British) South West Africa. Citizens of Britain and the British dominion of South Africa were entitled to residence, land purchase and, often, land bank loans. The new settlers were predominantly Boers who had lost their land and livelihood during the ravages of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). Obliterating ‘German’ in the country’s name meant that Germans could be expelled as undesirables. Locals often made use of the new government’s temporary administrative indecision and the intention to play the liberal card. They regained some land and livestock and, though in vain, hoped that the British would initiate general restitution.

The League of Nations’ mandate system, established in the Versailles Treaty of 1919, forbade victors to annex the defeated enemy’s colonies. A mandatory or trust power under international supervision was implemented to administer the inhabitants until they were able to govern themselves. The ‘victors’, however, did not return land or sovereignty to expropriated Africans. On the contrary, under South African/British rule white-owned farmland expanded. Years later, the National Party’s 1948 election victory would lead to the Group Areas Act and the Odendaal Plan that created ‘homelands’ for South West African ‘tribes’; the culmination of the trend that had started in 1915.

At the time of the arrival of the Hill, Walser and Hartung families, people still tended to interact as equals and patterns of coexistence were developed.

(Join us every Sunday to take a step back in time and follow the interesting, sometimes sweet, sometimes heart-wrenching tale. If you miss any of the chapters, follow our links to the PadlangsNamibia website, where we will make them available for you.)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT