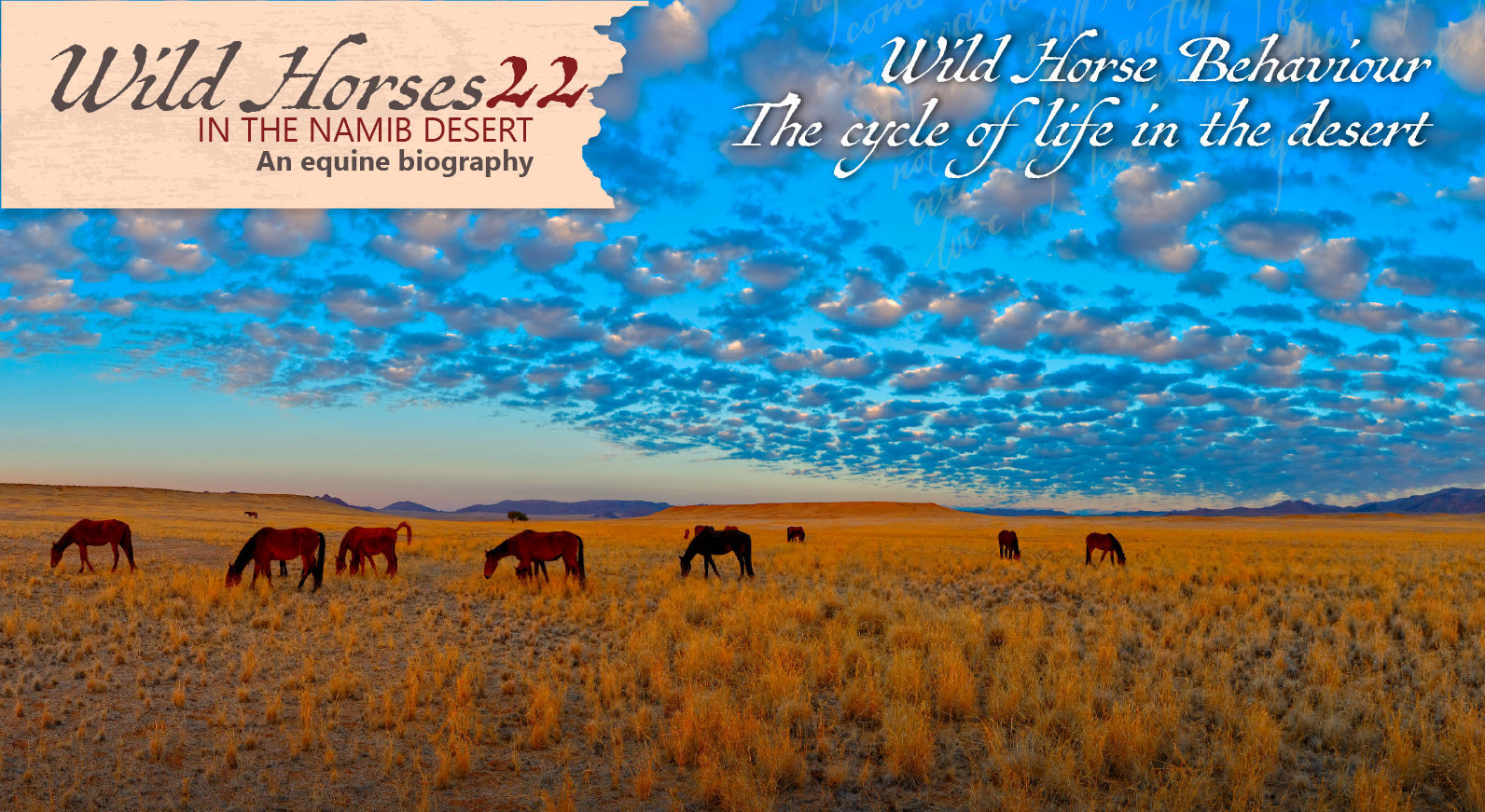

Set in southern Namibia, Great Namaqualand, ‘Bittersweet Karas Home’ is the story of three families, the Hills, Walsers & Hartungs, whose lives merge and intertwine in a semi-arid land that presents both hardship and blessings. Over the next few months, we would like to share this bittersweet saga with you from the (as yet) unpublished book.

CHAPTER ONE (cont . . .)

Transcontinental rinderpest

One of the worst disasters that affected Africa originated in the Ethiopian port of Massawa in 1887, its repercussions to later claim the life of a Hill. Italians unloaded Asian cattle infected with the cattle plague rinderpest, also called steppe murrain. The virus was transmitted from animal to animal by air and by drinking contaminated water. It spread to wild animals like buffalo, eland, giraffe, warthog and kudu and was re-transferred to domestic stock. The animals had high fevers, runny eyes and noses, and suffered terribly for a week, finally dropping to their knees and toppling sideways under the eyes of the wary vultures circling overhead. The disease travelled a few miles every day. Forested areas and well-flooded rivers slowed it down but did not stop it. It spread in all directions, but the Rift Valley channelled it mainly in a southerly direction.

Pastoralists without their staple products of milk and meat starved or succumbed to diseases like malaria, smallpox, cholera and typhoid, which their starving bodies could not resist. Animal carcasses rotted everywhere. Landscapes were steeped in eerie silences. Some villages displayed no signs of life. Bones glistened like maggots in the sun. Wagons lay still. The survivors struggled to find an explanation for this ghastly visitation, but there was no collective memory to explain the horror and no traditional cure was known. Further south, European vets were also dumbfounded but rinderpest had haunted Europe for centuries and they knew crude containment measures: slaughter, quarantine and the erection of border fences and barriers. Africans did not trust these measures and often believed that the disease had been transmitted by the Europeans.

The lack of settler empathy and the increase in African resentment made uprisings after cases of veterinary cattle slaughter, followed by military responses, inevitable. The Matabele rose in 1896, and the Batswana and the Afrikaner Oorlams in 1897.

In Namaqualand, as part of the rinderpest regulations, a five-mile cattle-free zone at the border to Gordonia was established. Cattle found in the vicinity were either shot or confiscated. All pastoralists - whether white, brown or black - were affected by the outbreak. It was only the promise of compensation that cushioned the blow.

The pastoralist-raider lifestyle of the Afrikaner Oorlams, who lived between the Great Karas Mountains and the Orange River, was threatened. They rebelled and raided livestock on the German and the South African side. This caused the German Schutztruppe and the Cape Mounted Rifles to retaliate. As the Afrikaner Oorlam raids were undiscriminating, they also angered Bondelswarts, Veldschoendragers and many settlers. The vivid memories of the Oorlam reign of terror in the early nineteenth century resurfaced. Although James Henry Hill volunteered to fight against them, his involvement did not express his unconditional support for the Germans but rather a farmer’s dread of livestock theft.

Ukamas, which was 40 kilometres or eight horseback hours to the south, was the headquarters for the campaign against the Afrikaner Oorlams, who had chosen Xamsib Kloof at the Orange River as their mountain fortress. On 15 July 1897, after a ride through the night, 17 German soldiers arrived at the ravine at sunrise and confronted 100 Oorlams. The Schutztruppe approached the enemy positions, forcing the Oorlams to retreat several times but did not gain control. Two German soldiers were fatally wounded. When Charles Wheeler junior, a volunteer and son of an early British settler, reported that he had overheard Namas planning to separate the soldiers from their horses, the soldiers engaged in a dangerous uphill retreat and withdrew to Ukamas. The Oorlams’ excellent marksmen and landscape-savvy warriors had outwitted the Germans, who paid dearly for underestimating them.

A force of 102 combatants - among them James Henry Hill - returned to Xamsib ravine on 2 August, this time armed with a Mountain Howitzer for siege purposes. The German advance surprised the Afrikaner Oorlams because the wind created a buffer blocking out the sound of approaching horses. The Germans had been told by Nama spies where the Oorlams had dug in. The cliffs and the rocks in the riverbed and on the plateau - cracks, crevices and crannies - provided concealment for rifles and riflemen. Lieutenant Von Altrock, James Hill and Rider Ewest began the attack from the plateau next to an almost vertical cliff, before making a dash down to the riverbed. As Von Altrock advanced towards the enemy position, he was shot in the head and died immediately, as did Rider Ewest. James Henry Hill dropped into a protected space between boulders after a shot pierced the tip of his left lung. He waited for another shot that would end his life but only experienced a scrape to his side from a bullet that ricocheted from the surrounding rocks. The pain from the wound in his chest was intense and he soon lost consciousness as the blood seeped out of his body. If he had met the man who shot him a few months before while waiting for the ferry at Ramansdrift they would have chatted about the rain, cattle prices, transport driver wages and the river snake. They would have joked about Timothy Snewe’s great thirst and would have found out that they knew the names of a few dozen acquaintances they had in common. Now they fired at each other because their leaders had failed to draw up a common plan for the war against the plague.

When nightfall came, the Oorlams slipped away. The Germans retrieved the wounded, James Henry Hill amongst them, and their dead. Dr Paul Schöpwinkel and four assistants treated James Henry immediately and managed to stem the blood flow. Unfortunately, his wound was too severe and James died on 5 August 1897.

A horrifying and freakish accident occurred during the battle. A dog that had been wounded in the barrage crept, whimpering, into a cave where Oorlam women and children were hiding. A German soldier, unaware of the hiding place and possibly to end the dog’s pain, aimed the cannon and released a shrapnel bomb that exploded in all directions, killing the people huddled at the entrance to the cave. Today, Xamsib Kloof is referred to by locals as Meide Kloof or Women’s Ravine.

The Oorlam men who had escaped were captured by the Cape Mounted Police and handed over to the German soldiers. There was none of the German leniency the Witboois had experienced three years earlier. Twenty men received death sentences. Missionary Tobias Fenchel was there on execution day to offer spiritual solace, a small consolation to the men’s families.

The Hills and Walsers mourned James Henry’s death. Blaming Von Altrock was futile because he, himself, had paid the ultimate price. He was not unfamiliar with the terrain because he had been on an expedition to the Orange River only half a year earlier. They pitied the Afrikaner Oorlams, especially those they had known personally. They appreciated Dr Paul Schöpwinkel’s life-saving efforts and kept up the communication with the Schöpwinkels for decades afterwards. The Hills and Walsers feared that the Germans had created a situation that would escalate out of control. They remained loyal to their Bondelswarts and Nama hosts while the Germans entered into more intense conflicts. Draconian measures would not prevent the Nama from holing up in the Karas Mountains in the event of clashes. The rumble of war had come threateningly close and they were deeply worried. Little did the extended Hill family know that the 1903-1908 Nama/Herero-German war, the World War and, more indirectly, the Anglo-Boer War would be on their doorstep within the decade.

(Join us every Sunday to take a step back in time and follow the interesting, sometimes sweet, sometimes heart-wrenching tale.)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT