The early Farmers of the eastern Fish River Canyon

In the 1950s intrepid families trekked to the rugged and arid eastern reaches of the Fish River Canyon where they persevered in the arid environs. Among these families were the De Waals; their farm was Augurabis – ‘The place of much water’.

Augurabis was the first farm purchased by the forerunners of Gondwana in 1995. This would be the seed that would grow into the hospitality company, Gondwana Collection Namibia. As another ten farms were gradually acquired over the decades, it would also grow into the 130 000-hectare Gondwana Canyon Park, one of the largest privately-owned conservation areas in southern Africa. The fences were dismantled and wildlife was reintroduced, rewilding an area that had been left barren after years of drought, intensive sheep farming, and hunting. The vegetation slowly recovered, as did the wildlife that without fences could now follow the scattered rainfall. I met many of the old farmers who were finally giving up the struggle, selling their land and moving to the towns. We did not have the good fortune to meet some of them, but we slowly discovered the fascinating stories of their farms and families.

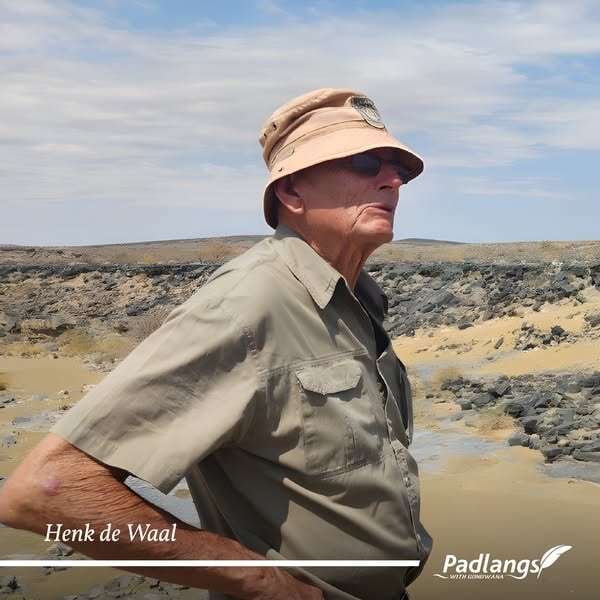

We could trace Augurabis’s story to Oupa Hendrik de Waal. We met his grandson Hendrik (Henk) and his wife Marianne and they recounted the story under the thorn trees at Augurabis and over melktert and coffee at their diningroom table in Springbok, filling in the gaps and generously offering intriguing and amusing anecdotes about life on the farm in the 1950s, 60s and 70s.

Their story begins a hundred years ago with Oupa Hendrik (born in 1916 in Beaufort West), his wife and son Daniël Jacobus, who was about seven years old at the time. The De Waals were subsistence farmers, barely scraping together a living in the Union of South Africa. After WW1, in the early 1920s, the De Waals, together with other South African families, gathered their belongings and trekked north. Their destination, South West Africa.

They crossed the Orange River at Vioolsdrift and continued north, aiming for Gibeon and the adjacent land where a large group of ‘trekkers’ and locals had already settled. Oupa Hendrik and his family trekked north on donkey carts and mule wagons with their Afrikaner sheep, some goats and a horse or two. The family was on the ‘trekpad’, following the Fish River northwards, for over a year before they reached the wide, sparsely populated country of the Gibeon area, south of Mariental. This was where they eventually met up with the Van Niekerk family that had originated from Kenhardt in the Northern Cape and had entered South West Africa from the Keimoes-Kakamas region in 1925. Daniël had his first chance to cast eyes on the four Van Niekerk daughters, merging the destiny of the two families.

Daniël spent the rest of his childhood there, marrying Johanna (Hannie) van Niekerk in 1941 during WWII. All commodities were scarce or rationed due to the war. Daniël and Johanna lived with the De Waal family, scraping a living from communal farming. Daniël picked up work as a contract labourer on the railways for the South African administration. The pay for hard labour was six pennies to one shilling per day.

When Oupa Barend van Niekerk (Daniël’s father-in-law) decided to trek south, the young couple joined them. In the late 1940s the family reached the farm Vergelegen, east of the Fish River, adjacent to the farm Augurabis which would later become Daniël and Johanna’s home. Their eldest son Hendrik (Henk) was born in Keetmanshoop in 1944.

While they trekked southwards, the De Waal family trekked northeast into the Kalahari, ending up after the war on the farm Eindpaal.

On Vergelegen Oupa Barend presented the young couple with grazing rights. Initially they lived in a bell tent on the land and had a wagon with tyre-wheels drawn by donkeys as their primary transport. During this time Daniël worked as a contract worker drilling boreholes at an outpost near Vergelegen. The family trekked with their livestock from one grazing area to another.

Choosing to make a start away from their in-laws, Daniël and Johanna bought the farm Augurabis, opposite Vergelegen, using their stock as collateral. They applied for a grass licence and moved with their two small children, Henk and Barend, who was born in 1946.

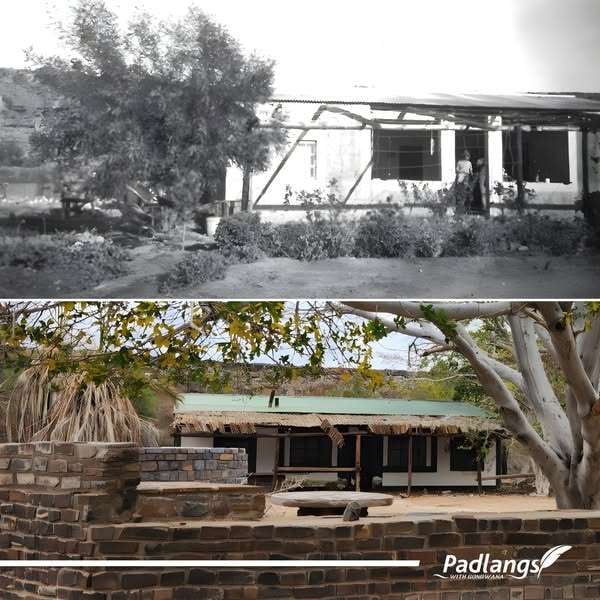

Their first home was the bell tent and a corrugated iron house which they reassembled and where the veranda served as a cooking area, until they could build a larger house. Daniël built a shower complete with a shower head, using a jam tin and four-gallon paraffin can, soldering iron, rope and a pulley over a beam, cordoned off with poles cut from the surrounding vegetation. With the help of labourers, he began the backbreaking work of building roads in the stony land around the farm.

Henk was a young child then and remembers how they started from scratch, digging a well and planting vegetables and fruit trees. He and his brother went to boarding school in Keetmanshoop, returning home in the holidays when they had to help out on the farm. Henk says: “We were poor but we were healthy, disciplined children and we were happy.” Blessed with water, Augurabis enabled the family to grow grapefruit, naartjies, oranges (“the best in southern Namibia,” according to Henk, “because of the lime in the soil”), figs, lucerne, pomegranates, grapes, sweet melons and a variety of vegetables, which had to be protected from the birds and baboons, and which Daniël took, in season, to a fruit-and-veg shop in Keetmanshoop to sell.

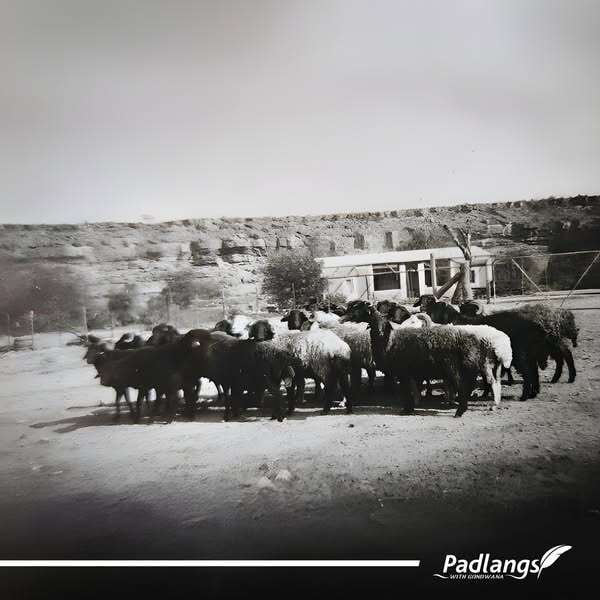

They also started farming karakul sheep, selling the pelts to the co-op in Keetmanshoop. During the 1960s Pa Daniël worked on breeding a white karakul stud. The white pelts were rare and sought after. The family was mostly self-sufficient, eating goat meat, hunting for the pot and eating the fruit and vegetables they grew.

The sheep needed to be sheared at least once a year. A group of neighbouring farmers would rotate the shearing season activities. The farmer who sheared first would collect the shearing team from their homes and the last one would take them back home. A team usually consisted of eight to ten shearers and some of them came from as far away as Berseba, near Gibeon. In the early 50s a sheep was sheared for as little as a tickey a head, eventually ending up at more than a shilling a head plus a sheep for meat for the team. Large hessian bags for the wool were hooked up between four evenly-spaced posts. The children would serve as ‘woltrappers’, stamping the fleece into the bags.

The family made their own soap and biltong. Henk recalls that when they slaughtered a sheep or goat, they would string up the carcass during the cool of the night and at first light put it in a ‘skottel’ (a big dish), cover it well with blankets and put it under the bed or in the cooler. This was the task for the children when they were home from school. “There was no early to bed or sleeping late,” Henk remembers. They built a cooler with burnt coal from the Holoog railway station, trickling water through it to keep it cool. Henk laughs and recounts the story of the time when 24 quart-bottles of ginger beer exploded one day when they put too many raisins in the bottles.

Daniël and Johanna kept some cows for milk and kept chickens for eggs behind the house in a ‘hoenderhok’ under the false ebony trees. The chickens would sometimes disappear, only reappearing when they were hungry and their eggs were ready to hatch or when their fluffy chicks would follow them in. In the 1960s milk and buttermilk were also part of the family’s daily fare.

(Join us tomorrow for part 2 of the Augurabis story).

.png)

.png)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT