Set in southern Namibia, Great Namaqualand, ‘Bittersweet Karas Home’ is the story of three families, the Hills, Walsers & Hartungs, whose lives merge and intertwine in a semi-arid land that presents both hardship and blessings. Over the next few months, we would like to share this bittersweet saga with you from the (as yet) unpublished book.

CHAPTER TWO (cont . . .)

𝐅𝐚𝐫 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐟𝐚𝐦𝐢𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐚𝐦𝐞

In Herisau, where Carl Wilhelm trained to become a merchant, and in St Gall everybody had known that he was Carl Adrian’s son. Many had heard about Johannes Walser (1752-1805), the Russian Walser who had become an art supplier for the Romanov Tsars while also being a linen merchant associated to the Merchants’ Guild of St Petersburg. He admired his father’s brothers: Julian Theodor (1825-1902) who emigrated to New York in 1851, studied medicine and was at the forefront of the battle against contagious diseases like smallpox and cholera in New York’s Marine Quarantine Hospital and in citywide campaigns; and his uncle, Ludwig Emil (1837-1910), who stayed with his father until the outbreak of the Civil War, becoming a partner in the Zähner & Schiess embroidery company and opening a branch for them in London. Being in the shadow of these Walsers was challenging and sometimes daunting.

After Carl Wilhelm’s departure, he was away from the Walsers but still under the Swiss company’s control. He could have returned to St Gall after the business failed but crossed the Gariep instead to lead a life beyond the Walsers’ influence.

Margaret Susan Hill liked what she knew about the Walsers and understood that Carl Wilhelm’s new life as a south-eastern Kalahari farmer was his way of becoming independent. Blissfully unaware of the enormous climatic and historical challenges that awaited him, Carl mustered his courage for the days ahead. The fact that nobody thought him suitable for this kind of life, not even himself, was merely another obstacle to overcome.

Carl Wilhelm was proud of being a Walser. This pride would soon be reinforced by the younger Walser generations: Robert Walser who achieved prominence in modern literature and Theodore Demarest Walser who was a missionary in Japan and later became a pacifist politician.

𝐀 𝐛𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩 𝐢𝐧 𝐇𝐞𝐢𝐫𝐚𝐠𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐬

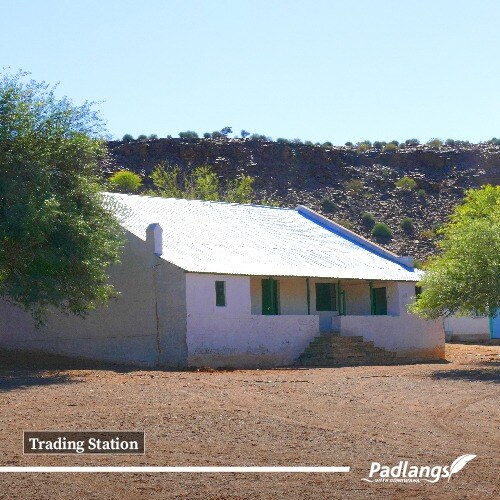

Charles Henry Hill took Carl Wilhelm under his wing and gratefully accepted the rifle and ammunition Carl had presented. Charles knew that the trader Ludwig Dominicus owned a shop in Heiragabis and that Ludwig’s partner, Harry Cole, had left after a clash with the Veldschoendragers. Perhaps his young guest had arrived at an opportune time.

A few days later Carl Wilhelm prepared the Cape cart. James drew a rough map of the route to Heiragabis but then decided to accompany him for the journey. James joked about the sideways glances between Carl Wilhelm and Margaret, saying, “So you really like her. Well, she thinks you are sophisticated. I wouldn’t be surprised if you ended up in the bosom of the Hill family.”

James told Carl Wilhelm about how the Afrikaner Oorlams had invaded the country more than 80 years before. The Oorlams were herders and raiders for the Cape Colony farmer, Petrus Pienaar, but accused him of meddling with their wives while they were out on assignments. When they confronted him, a scuffle ensued, shots were fired and Pienaar was killed. Cape courts wanted to bring them to justice and punitive commandos were organised. The Orange River islands between Upington and the Augrabies Falls were useful retreats. The Oorlams also built a semi-circular fortification called ǁKhauaxa!nas next to the Bak River in the Great Karas Mountains, extending for a mile from one point on the cliff to the other. A vast plain stretched southward. From that vantage point, they could spot the dust clouds from horseback riders hours before they arrived. When they did, they would find the Oorlams safely hiding behind formidable walls. For several decades the Afrikaner Oorlams had ruled the area between the Gariep and the Kunene rivers because they had mastered the raiding techniques learned from Pienaar and because of their military superiority as owners of horses, guns and ox-wagons. Their Nama and Herero adversaries now closed the military skill and technology gap, restricting the Afrikaner Oorlam rule to a small strip between the Kalahari and the Orange River. James related a less gruesome story from the Oorlam reign of terror.

In 1811, they razed Warmbad’s church to the ground because of a cattle transaction that had gone awry. The first female missionary, Sophia Burgmann, had imported a piano at great expense to accompany the congregation’s church hymns. The valuable object had been carefully hidden in the cemetery, safe from harm. It was detected in its hiding place when underground rumbles and tinkles were heard and was unceremoniously dragged out, smashed methodically and recycled as bow strings and other improvised tools.

They continued in an eastward direction from Kalkfontein. James told him that the name ‘Heiragabis’ referred to the acacia trees growing in the riverbeds or rather to the gum oozing from them where the bark had been cut. The gum was tear-shaped, light yellow and translucent and split the sun’s rays almost like a prism. It was edible and children enjoyed its sweetness. In times of famine, the gum was essential for Nama survival. Unfortunately, it attacked the teeth when eaten for long periods.

Carl wondered whether it was gum Arabic. He remembered his biology and geography teacher lecturing about Gummi arabikum, a sticky substance that can be dissolved in water and is used in the manufacture of cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and food. The bark of the tree is cut and the resin, the tree’s method of protection, can be repeatedly collected throughout the seasons. Sudan produced most of the world’s gum Arabic but the Mahdi (1881-1885) and Khalifa (1885–1899) regimes cut off Sudan from the world market. Heiragabis might have something of international interest to offer. Carl Wilhelm would one day write in a memo: ‘I … developed quite a large business in the gum of the thorn-trees. It was just a favourable time for it, as the supply of the world was very much diminished through the action of the Mahdi in the Nile valley. The quantities I managed to send away from Ukamas direct to London were for some years from 100 to 120 bags per year. The gum was packed into double bags and sorted into seven classes, which gave a lot of employment to the native women who received 1shilling 6 pence per day for their work. So there were no cases of starvation in dry years at Ukamas. I attribute this fact as a reason that the natives scarcely ever stole any stock from me. Nor was I ever afraid of my life in the different native wars’.

(Join us every Sunday to take a step back in time and follow the interesting, sometimes sweet, sometimes heart-wrenching tale.)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

SUBMIT YOUR COMMENT